Cultural Expression in Afghanistan: 1996-2021

"The fear is that this society will become just black and white...

that we will not have the beautiful diversity and beautiful

colors in this country anymore.”- Omaid Sharifi

Culture is the heartbeat of a society, the avenue through which its members express shared joy, pain, fear, hope and all emotions in between. Cultural rhythms pump life into the imagined collective, creating a shared sense of identity and belonging among a mosaic of diverse peoples. Almost nowhere has this proven truer than in Afghanistan, where varying degrees of limitations and freedoms on cultural expression throughout the country’s history have also played a key role in the perpetual negotiation of Afghan identity. Considering the Taliban’s recent return to power in August 2021, this article provides a history of cultural development in Afghanistan since the group’s first stint in power between 1996 and 2001.

Under Taliban rule in the 1990s, most forms of art, music, dance, cinema and other cultural expressions were outlawed as un-Islamic, and therefore antithetical to the Taliban’s main objective: to create a conservative Islamic society and Afghan identity rooted in extremist interpretations of Sharia law. During this time, instruments, paintings, film reels and other remnants of Afghan culture were destroyed, those caught engaging in activities such as playing or listening to music faced harsh punishment, and many Afghan artists, musicians and other cultural professionals either fled Afghanistan or went into hiding. The Taliban also destroyed cultural heritage sites across Afghanistan, ranging from its machine-gunning of the iconic fountain of Herat in 1996 to its notorious blowup of two colossal 1.5 millennia-old statues of Buddha in the Bamyan Valley in early 2001. In this era, with the exception of certain religious hymns, poems, literature and calligraphy, most cultural traditions developed throughout Afghanistan’s long history all but ceased to exist.

National Institute of Music, in Zürich in 2017. Source: BBC.

Following the US-led invasion and collapse of the first Taliban regime in late 2001, however, the country’s cultural sphere underwent a remarkable transformation.

With international support, a new generation of Afghan artists, musicians and other cultural professionals used their work to voice support for an Afghan identity rooted in freedom, equality and shared hope for the future. In the post-2001 era, cultural expression in Afghanistan thus doubled as an instrument of activism, at times symbolising the rejection of Taliban ideology among certain parts of Afghan society, especially in urban cities such as Kabul. During this time, cultural figures such as Roya Sadat (first female film director in Afghanistan’s post-Taliban history), Ahmad Sarmast (founder of the Afghan National Institute of Music), the Zohra Orchestra (Afghanistan’s first all-female orchestra) and Shamsia Hassani (first female graffiti artist in Afghanistan) also rose to international fame as advocates of this new identity.

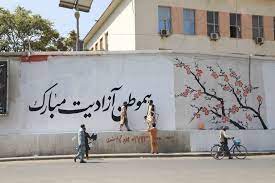

Since the Taliban’s lightning-speed takeover of Kabul and return to power in Afghanistan in August 2021, however, many have expressed fear that the previous two decades of cultural development and freedom in Afghanistan may have been all but erased in a matter of hours. Although the Taliban has pledged more social and cultural tolerance this time around, memories from the group’s previous era in power have rendered many skeptical of its promises, and the group’s recent actions also suggest another possible future for Afghanistan’s cultural identity. Notably, the Taliban has since August put forth concerted effort to remove well-known works of art from the public eye, closed down once-thriving centres of art, music, dance, and cinema, and also halted cultural performances. Many street murals in Kabul, having been deemed propaganda of Afghanistan’s previous US-backed government, have been either vandalised or painted over with messages such as ‘Ham Watan Azadet Mubarak’, aimed at celebrating Afghan independence vis-a-vis the departure of US troops in recent months.

Street mural in Kabul once honoring humanitarian doctor

Tetsu Nakamura was painted over by the Taliban in 2021. Source: Al Jazeera.

As a result, hundreds of Afghan artists, musicians and other cultural professionals have been among those that fled the return of Taliban rule in Afghanistan since August. Amidst a climate of instability and fear, many report having lost hope of sustaining their livelihoods in a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, and also fear the consequences of having publicly criticized the Taliban in recent decades, when the country’s cultural sphere doubled as a significant vector of socio-political change. Their departure symbolises a significant blow not only to Afghanistan’s cultural identity, but also to efforts aimed at reversing the crippling impact of the ‘brain drain’ effect on Afghan society in recent years. Among those who remain in Afghanistan, many have gone into hiding, engaged in self-censorship or even pre-emptively destroyed their own work - burning paintings, breaking instruments, smashing sculptures and/or deleting art-related files – for fear of retribution by the Taliban.

Nevertheless, the future of cultural expression in a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan post-2021 remains hanging in the balance. Rather than seeking to fill this gap of uncertainty with more speculation, through understanding the history of cultural development in Afghanistan in recent decades, this article has simply sought to draw attention to the oft-overlooked aspect of cultural freedom in discussions of how Taliban rule might impact Afghanistan’s future. Moreover, this article is meant to serve as a reminder that Afghanistan is not merely a desolate war zone home to passive and oppressed peoples, as it is commonly depicted to be by the Western media, but rather home to a vibrant and diverse society whose members – conservative, secular or a mixture of both – have played an active role in the negotiation and renegotiation of Afghan identity over time. As in any society, cultural expression - either through its limitation or flourishing – will thus likely continue to play a significant role in the determination of Afghanistan’s future.

Cover photo: Performance of the Zohra Orchestra, part of the Afghan

is a researcher of migration, nationalism, memory, identity and belonging in Southeast Europe and Central Asia. She holds a B.A. in International Comparative Studies from Duke University, and an M.A. in International Migration from the University of Kent.