Afghan Evacuees: What does the future hold?

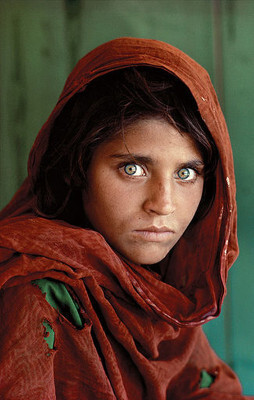

The Afghan Girl, a portrait of Sharbat Gula taken by Steve McCurry in 1984, is one of the most recognised photographs worldwide. In 1984, Gula resided in Pakistan’s Nasir Bagh refugee camp, having become one of millions of Afghans displaced in the Soviet-Afghan War. For decades, the Afghan Girl has symbolised the Western imagination of Afghanistan as a remote and war-torn country, also raising concerns over the seemingly perpetual plight of the Afghan people, and in turn, refugees worldwide. Throughout recent months, as the world continues to grapple with the reality of the Taliban’s unforeseen return to power in August 2021, concerns over the future of Afghanistan’s people have once again risen to the fore.

In August 2021, the world was paralysed by images of fear, violence and chaos unfolding outside the gates of Harmid Kazai International Kabul airport. After Taliban forces captured Kabul on August 15th, foreign governments scrambled to evacuate their own citizens before August 31st, the US’ self-imposed deadline for the withdrawal of all its troops from Afghanistan. Fearing a lack of security, the possible destruction of their livelihoods and/or various forms of Taliban retribution, hundreds of thousands of Afghans also rushed to the Kabul airport hoping to secure limited spots on foreign evacuation flights out of Afghanistan. On August 26th, a bombing claimed by ISIS ripped through crowds gathered outside Abbey Gate, wounding and killing hundreds of Afghans and dozens of US soldiers. While many Afghans were evacuated on those flights, many were ultimately left behind.

On the one hand, media images of these events offered a window of reality into the panic that enveloped much of Afghan society after the Taliban’s return to power in August. On the other hand, their widespread circulation, often without the provision of deeper context, also generated several misconceptions. In the Western media in particular, these images created a misconception that the majority of Afghans not only desire to leave Afghanistan, but also strongly oppose the Taliban. It must be acknowledged, however, that those Afghan refugees who have fled the country since August make up but a tiny minority of the Afghan population. Moreover, among those that chose not to flee, some even prefer Taliban rule to alternative forms of governance, their support for the group stemming in no small part from grievances aimed at the US, the previous Afghan government, and other foreign occupiers in Afghanistan.

Hundreds of Afghan citizens in Kabul crowded into a US military evacuation flight in August 2021. Source: The Guardian.

In addition to this imagery, numerous media reports urging Western governments to protect and save Afghans from the Taliban, celebrating the evacuation of various groups of Afghan refugees from Afghanistan, and also expressing grave concern for those left behind have also emerged in recent months. Moreover, much of the Western media has focused on sharing the stories of a select few Afghans who have been offered special visas, educational scholarships or other forms of institutional support aimed at fostering their resettlement in the West, and in turn, comparing their present circumstances to their past circumstances in Afghanistan. As a result, the Western media has largely portrayed Afghan refugees who have been resettled in Western countries since August as the recipients of transformed and limitless futures, with little to no acknowledgement of the hardships they faced either in recent months or are likely to face in the future.

Moreover, not only have recent media images and reports on Afghanistan ignored the irony that decades of Western meddling in Afghanistan have played a significant role in bringing Afghan refugees to their current plight, but much like Steve McCurry’s image of the Afghan Girl, have in many ways also reproduced the Orientalist narrative of the dominance of West over East. Additionally, they have largely neglected the fact that just like other forced migrants around the world, Afghan evacuees – privileged or not - are likely to face significant socio-cultural, economic, psychological and bureaucratic barriers in the future, regardless of their countries of resettlement. In addition to these barriers, they will likely be heavily impacted by anti-migrant sentiment that runs rampant worldwide, and in Western societies in particular, impacts those of Muslim origin in a more extreme manner.

With or without Taliban rule Afghan society is deeply religious and conservative, and even the most secular Afghans tend towards a level of conservatism greater than is the norm in many Western countries. As a result, this is likely to have a particularly significant impact on future socio-cultural challenges and rates of discrimination faced by Afghan evacuees resettled in Western countries. Indeed, this has already been foreshadowed by some Western politicians, who in recent months have expressed security and various others concerns over the impact of resettling Afghan – and primarily Muslim - refugees in the West. For some Afghans, such high rates of discrimination abroad have also acted as deterrents contributing to the prevention of their flight from Taliban rule. According to Ahmad*, an Afghan citizen in Kabul, “Foreigners don’t like us [Afghans] to come to their country…it’s a thing that makes me stay here [in Kabul], because I don’t want to bother them just because I’m not safe here.”

Acknowledging this reality is not to say that concerns over the future of Afghanistan lack legitimacy, nor that the Taliban doesn’t have a history of violence and oppression aimed at the Afghan people, especially women. In fact, as the resurfacing of the image of the Afghan Girl has reminded us time and again, Afghanistan has long before August been one of the most emigrated-from countries in the modern world. Moreover, the above points are not meant to question the reality that the lives of many Afghan refugees may have indeed been saved in recent months, nor that many Afghans now settled in Western countries – especially women - are likely to experience more freedom and opportunity in the future. Nevertheless, it is crucial to acknowledge that rather than having simply reached happy endings, as recent media coverage might suggest, their stories are only just beginning. Moreover, the choice to flee one’s country cannot be confused with the desire to flee, and as is visible in the plight of Afghan refugees in recent months, the lines between forced and voluntary migration are often more blurred than we tend to imagine.

*name changed to protect identity

Cover photo: Girl, Steve McCurry's portrait of Sharbat Gula at the Nasir Bagh refugee camp in Pakistan in 1984. Source: The Guardian.

is a researcher of migration, nationalism, memory, identity and belonging in Southeast Europe and Central Asia. She holds a B.A. in International Comparative Studies from Duke University, and an M.A. in International Migration from the University of Kent.