A brief history of the position of women and girls in Afghanistan

The recent Taliban take-over has remained in the headlines in the past weeks, raising many concerns about the future of this land-locked, war-ridden country. The position of women and girls is especially affected under the regime of the ultra-conservative Taliban organization, which endorses a strict interpretation of Sharia Islamic law.

In most of Afghanistan’s modern history, women were subject to differing degrees of purdah – a practice of female seclusion that confines women to their homes and requires them to cover their bodies. It is for this reason that, as Dr. Huma Ahmed-Ghosh suggests, one must approach the analysis of women's situation not through the simple formulation of before and after the Taliban, but within the larger historical context. This article summarizes this shifting history of the position of women and girls in Afghanistan, to shed light on how the Taliban take-over may impact women and girl’s lives in this country.

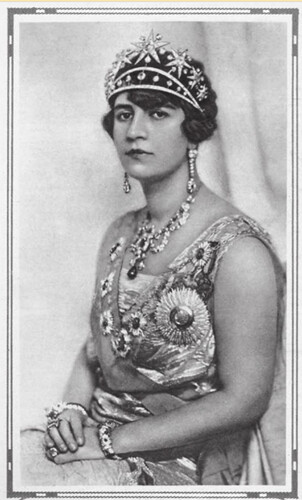

Patriarchal kinship norms, key in framing gender relations and control over women’s lives, are particularly strong in rural areas, where over 80% of the Afghan population lives. Throughout the 20th century, Afghanistan experienced a struggle between secular and religious forces and urbanite and rural movements. There were repeated attempts at “modernizing” Afghan society, such as those introduced by King Amanullah (1919 - 1929) and his wife and only Afghan woman ruler, Queen Soraya Tarzi. Their regime instituted education for girls, encouraged Western-style secular attire, and promoted women’s inclusion in public life, led by Queen Soraya’s own example – reforms that soon led to widespread opposition and the demise of Amanullah.

A second attempt at reforms concerning women took place in the 1940s and 1950s, with massive foreign aid and technical assistance from the Soviet Union. The PDPA regime, who thought it useful for the economy to include women in employment, forced a modernizing agenda of social change that led to the ten-year war between Afghanistan and the Soviet Union, the birth of the Mujahideen, and the decline, yet again, of women's status. In 1964 the third Constitution allowed women to enter elected politics and gave them the right to vote. But, it was in the 1970s that Afghan women experienced the greatest change in their status. A program of mass literacy for all, including women, was introduced, and women’s presence in universities, private companies and in parliament increased. A minimum age for marriage was set at 16 years for girls and the enforcement of the purdah was relaxed.

In 1989, when the Soviets left Afghanistan after a decade long occupation, the US-backed Mujahideen took over Kabul and reinstated Islamic rule. This meant another setback for Afghan women, who were now mandated to wear the burqa and began to disappear from public life. Yet, even stricter laws were to manage their lives several years later, when the Taliban (also backed by the US, together with Iran, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia) took power in 1996. For women, this meant no longer being able to go outside except to buy food, and only accompanied by a mahram (male relative). Women and girls could not go to school nor visit male doctors. Not unlike the Mujahideen, the Taliban too indulged in forced marriages and rapes, as well as public whipping and, occasionally, executions of disobedient women.

Since the Taliban were removed from power in 2001 following the September 11 attacks in the US, women saw a gradual improvement in their legal rights and became de jure equal to men under the constitution of 2004. Progress has been made in improving Afghanistan's education enrolments and literacy rates – especially for girls and women, with numbers increasing from almost zero enrolled girls to 2.5 million, and the female literacy rate jumping to 30%.

As the Taliban re-established their rule, many fear their take-over will setback civil liberties earned since their demise in 2001. It is important to mention, however, that most of the progress in the past two decades took place in the large cities. For many girls in the vast rural areas of the country, the shift in power will bring little change. The Taliban have pledged for a softer stance more inclusive of women this time around, and reactions to their take-over vary among regions. It remains to be seen how women will deal with the new reality of their status, and some resistance is already taking place.

Cover photo: Queen Soraya, published in the Illustrated London News, March 17, 1928. Source: http://phototheca-afghanica.ch

is a Marie Curie fellow in the European Joint Doctorate MOVES (Migration and Modernity: Historical and Cultural Challenges). She is based at Paul Valery 3 University in Montpellier, France and Charles University in Prague. Her doctoral research examines discourses on immigrant integration to understand how “integration” is imagined by various social actors.