Immigration and the integration of immigrants in Romania

Romania is a country of emigration, with the number of people leaving the country exceeding those entering. As a result, the literature and data sets tend to focus on the subject of emigration rather than on immigration. Thus little is known about the issue of immigrant integration in Romania; about the facilities provided by the Romanian state to encourage integration; and about the efforts that immigrants themselves make toward integrating in Romania. The integration phenomenon in Romania is quite recent, therefore the “consequences of migration” (Favell, 2003), or the experience of immigrants after their settlement in Romania, is a subject which only manifested itself in 2004, following the first law on immigrant integration for persons receiving a form of protection in Romania (refugees and people with subsidiary protection[1]).

The aim of this article[2] is to present the facts on immigration and immigrant integration in contemporary Romania. Firstly I will deal briefly with Romania’s post-1990 immigration context from the macro perspective. Secondly, the text will focus on some specific aspects of refugee integration, specifically of those coming from Cameroon and the Republic of Congo.

Romania’s immigration context

During the communist regime, immigration to Romania was a rather secretive affair, strictly controlled by the government. Following Lazaroiu (2003), there were two types of immigrants coming to Romania during the communist regime:

- Western foreigners: These generally came to visit their friends and families, and were strictly monitored.

- Students from African and Middle-Eastern countries: They were only allowed to enter Romania for study purposes. These students paid thousands of dollars for their studies and therefore provided a significant amount of hard currency to the state universities. Their studies were based on the bilateral agreements called ‘Treaties of Friendship and Cooperation’ between Romania (characterized by Ceausescu’s political involvement in the Third World) and other developing countries. For example, from 1973 to 1985, thirteen such treaties were signed with 10 African countries (Oprea, 2009).

We cannot speak about any significant migratory flow into Romania before 1989, but after this year Romanian borders became more permeable and foreign businessmen, refugees, irregular immigrants and victims of trafficking started to enter Romania.

After 1990, there are two major groups of migrants legally entering Romania:

- Voluntary Migrants: Businessmen, economic migrants, the family members of already settled immigrants, students. At the start of Romania’s application to join the European Union, another group of voluntary migrants entering Romania are Third Country Nationals who arrive in Romania on working visas. The presence of these foreign workers is, according to the Hamburg Institute of International Economics (HWWI, 2007), attributed to two causes: Romania’s economic revival, and the opening of the Romanian labour market in the context of the country’s EU accession.

- Forced Migrants: Asylum seekers and refugees, people with subsidiary or temporary protection (Necunoscutii de langa noi, 2006).

Voluntary/economic migrants in Romania

At the beginning of the 1990s, Romania had a relatively modest level of immigration. Entrepreneurs, especially from Turkey, the Middle East (Syria, Jordan) and China were the largest group of immigrants during this time. In 1993 the National Office of Labour Force Migration from Romania (within the Romanian Ministry of Labour, Social Solidarity and Family) identified the following main groups of business-related migrants in Romania: drivers and traders from Pakistan, salesmen from India, and Chinese cooks (HWWI, 2007; Lazaroiu, 2003:37).

These foreign business communities play an important role in the economy; but despite their contribution to the Romanian economy and to its society, the establishment of foreign businesses in Romania is regulated by strict measures. In order to avoid visa abuses that could lead to transit migration, the legislation relating to foreign investments has changed dramatically since the beginning of the 1990s, especially with regard to the minimum amount of investment that these immigrants are obliged to provide – compare 10.000 USD in 1990 to 50.000 EUR in 2003 (HWWI, 2007:4). As Lazaroiu (2003:8) argues: “It seems that economic investment in Romania by extra-European individuals draws attention to the aspect of border securitization as Romanian authorities want to discourage transit migration.”

The number of economic migrants arriving with a working contract based on bilateral agreements between Romania and other countries has been rising continuously. According to the HWWI (2007), only several hundred foreigners had been issued work permits by the end of 1996, but by the end of 2000 this number had grown to 1,580. The number continued to increase: from 3,678 in 2005 to 7,993 at the end of 2006.

Involuntary/forced migration

In Romania, the most significant legislative changes in the field of migration took place in the area of forced migration. Before 1991, when Romania ratified the UN Convention (1951) and the Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees (1967)[3], the legislative frame was provided by Law 25 from 1969 concerning the administration of foreigners in the Socialist Republic of Romania[4].

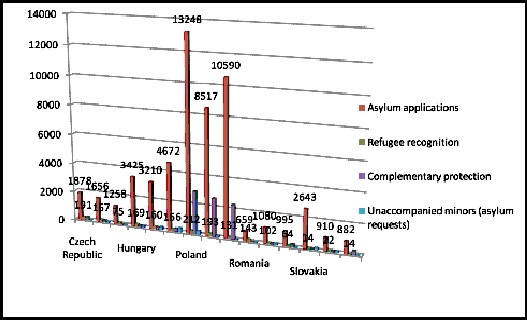

The graph below[5] shows that the recognition rate of refugees between 2007 and 2009, was around 10% or slightly higher (1,080 asylum applications and 102 cases of refugee recognition in 2008). Compared to other Eastern European countries such as Poland, Slovakia or Hungary, Romania’s recognition rate is quite high[6].

With regard to the countries of origin of refugees, the largest groups are from Iraq, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Somalia, the Republic of the Congo, Iran, Albania, Cameroon and Rwanda. The numbers fluctuate according to the political situation in the country of origin.

The instance of so-called refugees “sur place” merits special mention as it applies to many of the foreign students from African countries and the Middle East who were enrolled at Romanian universities during the communist regime and immediately after its dissolution. A person becomes a refugee "sur place" due to circumstances arising in his or her country of origin during his or her absence (Amnesty International, 2010). Many foreign students from the Republic of the Congo and Cameroon studying in Romania became “refugees sur place”, especially during 1997-1998 as a result of the civil war in the Republic of the Congo.

The experience of the Congolese and Cameroonian refugee communities suggests that integration into Romanian society depends on several factors: acquisition of the Romanian language; finding work; the level of support that refugees receive from both the Romanian and the African community; marriage with Romanian citizens and with co-nationals; and citizenship[7].

Most refugees from the Republic of the Congo and Cameroon expressed their belief that it was easy for them to learn the Romanian language due to the Latin/Romanic origin of both Romanian and French (spoken in Congo and Cameroon) as two refugees affirm:

“Romanian and French are similar in very many aspects. French being my native language, it was not hard for me to learn Romanian.” (refugee from the Republic of the Congo)

“I easily learned Romanian… In six months I could speak Romanian. I learned it on the street, from the TV, with my friends and colleagues.” (refugee from Cameroon, 40 years old)

Regarding economic integration, all the interviewed refugees stated that their integration into the labour market was similar to that of voluntary immigrants: they began in low-skilled/low status jobs, whatever their educational background, and advanced, in time, to better paid jobs with a higher social status.

“I did everything: that is why I could adapt here quickly. I played football until I injured myself; I had a stand at the market where I sold fruits and vegetables; I worked as a security agent; then I worked at a swimming pool; then I did some direct marketing for a company who finally hired me. Afterwards I opened my own construction company.” (refugee from the Republic of the Congo, 41 years old)

The social integration of refugees is framed by two elements: friends and marriage. The majority of the interviewed refugees stated that their Romanian friends outnumbered friends from the African community, because over time a large proportion of African refugees have left Romania for countries like Sweden, the Netherlands, Belgium, France and other countries.

“At first, I had many friends from the African community, but many of them left. And then I had Romanian friends. They were so nice that I couldn’t refuse them when they asked me to join them to play football, to attend funerals, parties, birthdays and so on.” (refugee from the Republic of the Congo, 41 years old)

In terms of the population spread of refugees, 80% of the total number of refugees registered in Romania reside in Bucharest. This may be because they studied in Bucharest for several years, and because the biggest economic opportunities are found in Bucharest. When it comes to marriage, most of the male African refugees I interviewed were married to Romanian women[8]. Only a small number of the refugees were married to persons from their own community.

As far as citizenship is concerned, in order to obtain it one must submit to a rigorous exam before a specialized committee. The conditions for receiving Romanian citizenship are the following: the applicant must be over 18 years of age; the applicant must prove 8 years of continuous residence in Romania; they must attest loyalty to the Romanian state through their behaviour, actions and attitude (i.e. they must not be linked to any hostile activities against the Romanian state); the applicant must have legal means to support a decent existence; they must not have been convicted in their country of origin or in Romania; they must know the Romanian language and be aware of aspects of Romanian culture and civilization; they must know the Romanian constitution and the national anthem[9]. The refugees that were interviewed considered citizenship as one of the most important steps toward their integration and the final one: “If you become a Romanian, then everything will become easier! Your status will change, getting a job will be easier, you can open a bank account, get a credit card, open your own company.” (refugee from the Republic of the Congo, 51 years old)

Conclusions

Although, in comparison to other European countries, the number of asylum seekers in Romania is still low, researchers, authorities, and policy makers argue that the number of asylum seekers and refugees in the country is set to increase due to the following reasons:

- Romania’s economic development (The Living Together Report, 2008:20, Lazaroiu 2003)

- Romania’s obligations under the Dublin II regulation (Living Together Report, British Council 2008:20) and an increasing emphasis on burden sharing in the EU (Munteanu, 2007) [10]. As approximately two-thirds of Romania’s borders are with non-EU countries such as Moldova, Ukraine and the former Yugoslavia, it is likely that a large number of asylum-seekers will enter through its territory.

Regarding immigration as a whole, Romania has gone through a status change in the last few years: once regarded solely as a country of origin; then a transit country and now a destination country (The Living Together Report, 2008). For example, the number of work permits being granted in Romania increased from 1,580 in 2000 to 1,704 in 2007, while the number of asylum seekers increased from 315 in 1991 to 995 in 2009. This increase in immigration to Romania was due to Romania’s EU membership and also to the directives of the Romanian National Strategy for Migration which aimed to meet demand for labour in the country by attracting foreign labour.

Bibliography

- British Council (2008) Programul Living Together, Equal opportunity and access in society, “Raportul Migrant Cities: Bucuresti”, www.britishcouncil.org/livingtogether;

- Centrul de Resurse pentru Diversitate Etnoculturala (2008) “Necunoscutii de langa noi. Rezidenti, refugiati, solicitanti de azil, migrant legali in Romania”, Raport realizat cu sprijinul Fundatiei King Badouin in cadrul programului “Minority Rights in practice in South Eastern Europe”;

- Favell, Adrian (2003) “Integration nations: the nation-state and research on immigrants in Western Europe, The multicultural challenge”, Comparative Social Research, Vol.22, 13-42, Elsevier Science;

- Hamburg Institute of International Economic HWW (2007), “Focus Migration. Country profile: Romania”;

- Lazaroiu, Sebastian (2003) “Sharing experience: migration trends in selected applicant countries and lessons learned from the new countries of immigration in the EU and Austria”, Vol. IV – Romania, “More out than in at the crossroads between Europe and the Balkans”; http://www.pedz.uni-mannheim.de/daten/edz-k/gde/04/IOM_IV_RO.pdf

- Munteanu, Alison (2007) “Secondary movement in Romania: the asylum migration-nexus”, New Issues in Refugee Research, Research paper no. 148, UNHCR Policy Development and Evaluation Service; http://www.unhcr.org/4766521e2.html

- Oprea, Mirela (2009), “Development discourse in Romania. From socialism to EU membership”, PhD Thesis; http://amsdottorato.cib.unibo.it/2228/

[1] Ordinance 44 from January 29 2004 regarding the social integration of foreigners who have been granted a form of protection or a right to reside in Romania, but also citizens of the EU member states and SEE states (Serbia, Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Albania and Montenegro)

[3] It also ratified the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (18th of December 1990); the Convention on the Rights of the Child (28th of September 1990); the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (20th of June 1994) and signed the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture (4th of November 1993)

[4] Published by the 1972 Official Bulletin, number 57, (Necunoscutii de langa noi, 2006)

[5] Source: Internal Statistics for 2010, The Romanian Immigration Office

[6] And comparable to that of the Czech Republic.

[7] This thematic analysis is based on 15 semi-structured interviews with refugees from Congo and Cameroon living in Romania. This research represents a work in progress, thus, other interviews will follow.

[8] 85% of the refugees I have interviewed until now, are men.

[9] Law 21 from March 1st, 1991, The law on Romanian citizenship

[10] Dublin Regulation (18 February 2003): the EU Council of Ministers adopted a regulation (343/2003/EC) establishing a series of criteria which, in general, allocate responsibility for examining an asylum application to the Member State that permitted the applicant to enter or to reside in the territories of the Member States of the European Union. That Member State is responsible for examining the application according to its national law and is obliged to take back its applicants who are irregularly in another Member State; Regulation 2725/2000 regarding the establishing of EURODAC; Regulation 2001/55/CE regarding the minimum standards of temporary protection in the case of a mass influx of persons and the states’ shared responsibilities.

Astrid Hamberger is a PhD student in the Department of Sociology at the University of Bucharest, Romania. She received her Masters degree from the University of Copenhagen. Her PhD thesis focuses on the integration of refugees in Romania.