Briefing 2: Family reunion policies in Central Europe

For whom is family reunion important in your country’s immigration system?

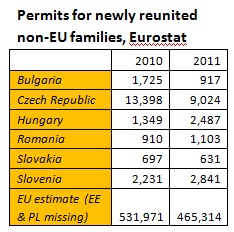

The countries where non-EU family reunion are most important are CZ, GR, NO, and SE. Since the financial crisis, non-EU family reunion has become more important in Southern European countries (IT, PT, ES) as the overall levels of new immigration have fallen in these previously major destinations for work migration. Non-EU family reunion is also important in Central European countries with very new and few immigrant communities, such as the Czech Republic and Slovenia.

Although the public associates family reunion with specific countries of origin, the list of top origin countries shows that families come from all over the world. Most recently reunited non-EU families in EU countries came from the world’s largest countries, Europe’s neighbours, and major countries of origin for immigrants settled in the EU. This top 10 list includes the major countries of origin for Europe, both near (Albania, Ukraine, Moldova) and afar (India, Pakistan, Ecuador). Rarely do most newcomer families in a given EU country come from one country, as is the case in Greece (Albanians) or Latvia (Russians), or from the same region, as is the case in Lithuania (CIS countries) or Slovenia (Western Balkans). The family members tend to be least diverse in new countries of immigration, such as Greece, the Baltics, and Central Europe.

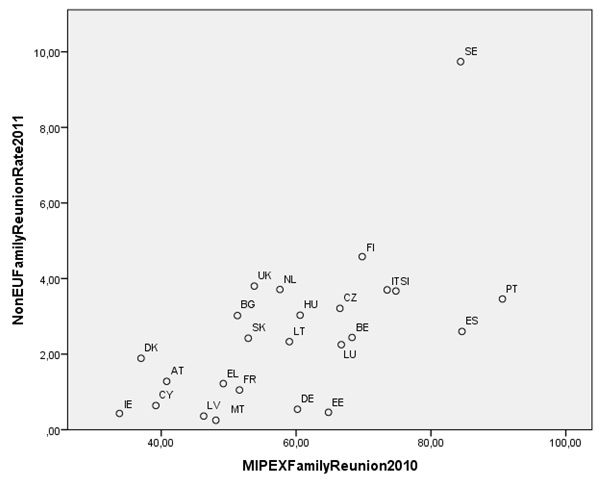

A very strong positive correlation emerges between the non-EU family reunion rate and family reunion policies for 25 EU Member States in 2011, as measured by MIPEX. A correlation means that the two are somehow linked: A country’s non-EU family reunion rate is strongly connected to its policy. Countries with more inclusive family reunion policies tend to have higher non-EU family reunion rates (meaning it is more common for third-country nationals to reunite with their families). These countries appear in the top right corner of the chart: Sweden, Finland, Italy, Slovenia, Spain, Portugal, and, to a certain extent, the Czech Republic, Belgium, Hungary, and Luxembourg. Countries with more restrictive family reunion policies tend to have lower non-EU family reunion rates. These countries appear in the bottom left corner of the chart: Ireland, Denmark, Cyprus, Austria, Latvia, Malta, Greece, France, and, to a certain extent, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Lithuania. This strong correlation across European countries holds for policies and rates in 2010, 2007/8, and for legal changes in 2011.

![]()

Q: How is non-EU family reunion affected by general changes in the country (e.g. economic crisis, immigration system, housing/welfare structures)?

Q: Are certain types of third-country nationals more or less likely to apply for family reunion?

What is the strategy behind your country’s family reunion policy?

"Family reunification is a necessary way of making family life possible. It helps to create sociocultural stability facilitating the integration of third country nationals in the Member State, which also serves to promote economic and social cohesion, a fundamental Community objective stated in the Treaty." Preamble 4 to Directive 2003/86/EC

The right to family and family life is enshrined in European and international law. EU Family Reunion Directive 2003/86/EC goes one step further to protect the right to family life by establishing the right to family reunion for non-EU sponsors and their families. Member States should provide third-country nationals with rights and obligations that are comparable to those of EU citizens. Facilitating family reunion facilitates immigrant integration and societal cohesion in economic, social, and cultural life. The Directive also aims to improve legal guarantees within the family reunion procedure for equal rights of men and women, the best interest of the child, and more favourable conditions for refugees.

The final EU Directive 2003/86/EC is a first-step harmonisation with valuable objectives and minimum standards for the 24 EU Member States concerned (Denmark, Ireland, and UK opt out). Not all Member States have properly transposed the Directive and its ‘shall’ clauses, according to the European Commission’s 2008 application report. These differences of interpretation between Member States, the Commission, and interested stakeholders are being addressed in cases before the European Court of Justice, from the European Parliament case C-540/03, Chakroun case C-578/08, to the recently withdrawn Imran case C-155/11.

The current Directive does bring some added value for integration. The Directive’s eligibility provisions and conditions are minimum, but fundamental. Most temporary residents now have a specific right to family reunion in the country where they legally reside, if they meet national legal conditions that are in conformity with the EU Directive. Under the Family Reunion Directive, third-country national residents can apply for at least most of their nuclear family. The Directive limits the duration of the procedure and the types of conditions that Member States can impose. Greater harmonisation was attained on the legal security of the family reunion status and the rights associated. EU law limits authorities’ discretion and the number of vague grounds for refusal or withdrawal of a permit. Rejected applicants have the right to a reasoned decision and judicial review. Accepted applicants have nearly the same rights as their sponsor to employment, education, and social programmes. Spouses and children reaching the age of majority are entitled to some form of autonomous residence permit after a maximum of 5 years’ residence.

The minor improvements brought by the Directive were most visible in new immigration countries in Southern and Central Europe, where little or no policy existed. In 2003, the then 15 EU Member States agreed to minimum standards on the aspects of family reunion where most of their policies were already very similar and strong. The rule of law and judicial oversight replaced administrative discretion in many elements of the procedure. The Directive has not only extended basic rights and legal securities to new immigration countries, but also secured them from future policy restrictions in all countries. In the EU countries where the Directive applies, most adopt slightly inclusive definitions of the family and only basic conditions for acquisition, out of respect for family life. MIPEX found in the majority of the concerned 24 EU Member States:

- Residence requirement for sponsors of one year or less

- No age limits over 18 years old for sponsors and spouses

- Some entitlement for family reunion for other dependent adult family members

- Basic housing requirement and economic resource requirement

- No language and integration conditions or pre-entry tests

Many of these countries may not have adopted these standards without the current Directive. For example, most of the European countries where the Directive does not apply (i.e. in the EU, Denmark, Ireland, the UK; outside the EU, Norway and Switzerland) contravene the Directive and obtain some of the lowest MIPEX scores on family reunion.

Family reunion policies in Central Europe are a mix of EU minimum standards and little national attention. Nevertheless, EU standards are largely behind Central European countries’ few areas of strength on integration policy. In other words, the facilitations that exist in family reunion legislation in Central Europe were mostly put there because of requirements from EU law. According to MIPEX, the legal frameworks are ‘slightly favourable’ for the reunification and integration of third-country national families in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia. Several more obstacles emerge in countries, such as Slovakia, Bulgaria, Lithuania, and Latvia. However, these countries ‘area of strength’ on family reunion may not demonstrate the government’s willingness to act on integration. The fact that these countries excel on these two areas may be as good a sign of national inaction as its poor scores in other areas. Because EU12 countries could not participate in negotiations of these pre-accession Directives, many felt little ownership of these new national laws. For low-priority and uncontroversial issues like family reunion and long-term residence, the method for transposition was to “copy-out.” In this case, policymakers take the national translation of the Directive and quickly pass it without changes or links to the broader legislative framework. Central European countries mostly copied the “shall” clauses and ignored the “may” and derogation clauses.

Because of these countries’ transposition strategies, little national thinking has gone into these country’s areas of strength, just like the three MIPEX areas outside EU competence: education, political participation, and access to nationality. Arguably, this inaction may matter little to immigrants themselves, who are still able to use their legal opportunities to reunite with their families and participate more in society. This limited planning behind these relatively new laws on family reunion can lead to problems with the implementation of the law and limited knowledge of these laws by public authorities. Indeed, problems with the rule of law and corruption emerge from the EU12 countries on the World Bank’s Good Governance Indicators.

While the future for immigrant families in Europe remains unclear with the current political climate and impact of far right parties, most Member States today still have policies that MIPEX finds are ‘slightly favourable’ for family reunion. The November 2011 European Commission’s Green Paper presented stakeholders with a new choice: either the Commission focuses on implementation of the current Directive (including infringement proceedings), or it reopens negotiations to change the Directive. Infringement proceedings have not yet been fully applied in the areas of legal immigration and residence. Re-negotiation has highly uncertain outcomes since the process may not lead to higher standards or harmonisation. On the contrary, the Netherlands lobbied the Commission and the Member States unsuccessfully for a renegotiation that leads to more restrictions, less harmonisation, and a fundamental change of scope. In the end, maintaining the current directive was the preference of nearly all Member States, international and national NGOs and ultimately the European Commission itself. Most Member States were satisfied with the current requirements and not interested in greater guidance from the European Commission or greater compliance from other Member States. Most international and national NGOs did not believe that a renegotiation process in the current political climate would lead to more inclusive EU or national laws. Instead, they called on the European Commission to ramp up its enforcement of the current EU standards including through infringement proceedings, its monitoring of compliance in national procedures and practices, and greater guidance, information exchange, and funding. The Commission has decided to develop its own ‘Interpretative Guidelines’ on the proper implementation of the Directive, receiving input from both Member States and EU-level NGOs. The Commission plans to publish its Interpretative Guidelines as a Commission Communication over the summer of 2013. These guidelines will provide the Commission the basis and scope for further action on family reunion in the next few years. These guidelines will provide the Commission the basis and scope for further action on family reunion in the next few years.

Q: How can organisations working on integration better monitor and improve the implementation and strategies behind the existing law on family reunion? How can they use the EU family reunion directive to improve implementation?

What are the real strengths and weaknesses in your country’s family reunion policy?

The Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) found that Member States generally perform better and similarly in areas where EU Directives apply, such as family reunion and long-term residence. The Visegrad countries generally have a slightly inclusive definition of the family for ordinary third-country national sponsors, according to MIPEX. Ordinary applicants can apply for their spouse and minor children, as well as, upon certain conditions, for their adult children, parents, and grandparents. The conditions are slightly more restrictive for adult children and parents/grandparents in Poland and Slovakia and for parents/grandparents in Hungary. Instead of spouses, registered partners can be sponsored in the Czech Republic and Slovenia, similar to around half the EU countries. The Czech Republic is the only Visegrad country to impose a minimum age limit for spouses and sponsors (20 years old) that is above majority age. Existing research does not suggest that such higher minimum age limits are proportionate or effective for promoting integration or fighting forced marriages (Huddleston, 2011).

MIPEX finds that countries increasingly disagree about what requirements should be imposed on immigrant sponsors and reunited family members. In the Visegrad region, the family reunification conditions are also 'slightly favourable' for ordinary third-country national sponsors. The housing and economic resource requirements are usually basic, but vague. Applicants often face high costs, not only in terms of the official fee but also all the costs of the documentation and travel for the family. Moreover, the family reunification procedure is often rather discretionary in Central Europe, particularly in countries like Hungary and Slovakia. The procedure involves additional vague grounds for refusal or withdrawal, such as public policy, security, or health. Furthermore, authorities in countries like Hungary, Poland, and Romania are not legally required to take due account of key aspects of the family's personal circumstances.

The MIPEX assessment also reveals that national laws in Central Europe also contain a few key weaknesses in the rights of ordinary reunited third-country national families. Generally, adult family members should receive equal access to education, training, social assistance, healthcare, housing and employment in most countries, but some limitations exist in countries like Hungary and Slovakia. Limited access to a residence permit autonomous from their sponsor is a major weakness for integration across Europe. The spouses and minor children of sponsors often have an easier access to the residence permit than other adult family members. Rarely do victims of domestic violence have a legal right to such a permit.

This table summarises key national findings on family reunion from the 2011 MIPEX and the Commission’s 2008 Application Report (see following table). MIPEX identifies the policy strengths and weaknesses for the Directive’s objectives on family reunion, integration, and equal treatment. The Application Report identifies areas of potentially incorrect transposition of the Directive.

Q: What practical problems arise during the procedure of family reunion? What types of third-country nationals are more likely to have problems in the procedure or be rejected?

Q: How could more support be created within the administration to promote the right to family reunion?

Q: How can the rules be made more clear and less discretionary?

|

|

Obstacles to integration of reuniting

families |

Problematic transposition of EU family

reunion directive |

|

EU-wide problems |

1) Countries with restrictive definitions

of family also impose burdensome conditions. |

1) Incorrect transposition in areas like

visa facilitation, autonomous permits, best interest of child assessments,

legal redress & more favourable provisions for refugees. |

|

Bulgaria |

1) Restrictive family definitions (adult

dependents) |

1) Mandatory provisions for minor

recognised refugees not yet implemented |

|

Czech Republic |

1) Requirement of permanent residence

permit |

|

|

Hungary |

1) Very discretionary procedure &

grounds for refusal & withdrawal |

1) Need obligatory mention of best

interest of children during application examination |

|

Poland |

1) Two-year-waiting period for

application |

1) Housing requirements cannot be imposed

on refugees |

|

Romania |

1) Very discretionary procedures &

wide grounds for refusal & withdrawal |

1) Public health ground to wide to comply

with Directive |

|

Slovakia |

1) Potentially high housing requirements

& fees |

1) Fees are too high if they undermine

Directive's effect on right to family reunion |

The article has been written as part of the project Migration to the Centre supported by the Europe for Citizens Programme of the European Union and the International Visegrad Fund.

This article reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Thomas Huddleston is a policy analyst at Migration Policy Group, working on the Diversity & Integration Programme. His focus includes European and national integration policies and he is the Central Research Coordinator of the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX).