Turkish Berlin: Integration Policy & Urban Space - Book Review

Hinze, Annika Marlen. Turkish Berlin: Integration Policy & Urban Space. University of Minnesota Press 2013 201 pp.

In what could be regarded her debut in the academic book world, she focuses on the discourse considering the Turkish community in Germany, specifically in Berlin, and aims to recognize the factors that affect the process of their integration. As she explains, "[b]y examining the microcosm of two Berlin neighborhoods densely populated by Turkish immigrants, I explore how a broad spectrum of local Berlin policy makers on one hand and German Turkish residents on the other hand interpret integration, refer to it, and apply it to daily life and urban policy making" (p. xvi). The following review aims to evaluate her endeavor.

The topic of integration is a rather complex one and while reading Turkish Berlin, one gets the idea that it resembles a puzzle that is made of many different, yet interlocking, pieces. In order to capture its intricacy, Hinze uses a dual perspective. On one hand, she is curious about how immigrants are framed and conceived of politically and on the other, she tries to find how immigrants perceive themselves and the ways they practice their daily lives (pp. xxi). Moreover, she combines the aforementioned perspective with a spatial approach to integration. For Hinze, urban space is much more than a marginal component of social reality; it is a lens for understanding social processes and power relations. But before she gets into the first stage of her research, she offers a very detailed and knowledgeable overview of the political evolution of citizenship law and the history of the Turkish community in Germany. Therefore, even those readers who are not familiar with German immigration discourse can quite easily comprehend the context of the following research. Without this very detailed introduction, one could hardly understand the importance of the abandonment of the German citizenship model in 2000, or how the 1973 oil shock affected the relation of the majority population towards the Turkish unskilled die Arbeiter who used to be welcomed in Germany under the guest worker agreement since 1961.

After the theoretical introduction and historical overview, the author moves towards the actual research. In the first stage, which could be labeled as How are immigrants talked about?, she analyzes a series of interviews conducted with political officials. Hinze is trying to find how local policy makers and government bureaucrats, such as members of the Berlin senate and the representatives for integration matters in Kreuzberg and Neukölln (the two districts with the highest percentage of immigrants), approach the concept of integration. Afterwards, she interviews Turkish community representatives, specifically speakers for the TBB (Turkish Union Berlin-Brandenburg) and Turkish public figures in Berlin's political scene. What she finds out is that there is a large disconnect between official political parties’ programs and statements on the one hand and the opinions of individual policy makers on the other. There are large numbers of policy makers who show understanding and compassion when it comes to the experiences of immigrants. Those are either young educated policy makers of immigrant background or civil servants that have been active in the integration field where they gained intercultural competence. Together with Turkish community representatives, they cultivate the immigration debate. Nevertheless, as Hinze immediately adds, culturally competent policy or public figures still remain a minority. The political parties fear a decline in voters’ support and therefore they generally refuse to address the critique of the exclusion of immigrants in the public debate. Such reluctance affects the mainstream media discourse that is often xenophobic towards the migrant communities, especially the Turks. Although they usually face discrimination based on their ethnic origin, the Turkish community is mostly connected to negative symbolic images regarding Islam, such as honor killing or forced marriages. "They create a powerful negative frame for this particular group in German society. These events are rare, yet they are standard framing referents of the Turkish community for mainstream ethnic Germans" (p. 35). As Hinze points out, policy and subsequently media discourse have real consequences for the Turkish community and the way they are perceived by the German majority. Instead of discussing the strong and weak spots of different integration policies, the public debate often identifies the Turks as those who are unwilling to integrate into German society. In other words, they are held responsible for their own exclusion.

In the second part of the book, Hinze takes the reader to Kreuzberg and Neukölln, two of Berlin’s densest immigrant neighborhoods, and shows how the general political concepts of integration work in spaces beyond the public gaze. Through several interviews with diverse women of Turkish origin, she adds yet another perspective that helps us understand the issue of integration in its complexity. The gender-dimension is more than important in Hinze’s approach. Since women now play a more and more significant role in the ongoing discussions regarding integration, she perceives them – literally – as a focal point of this issue. "They are seen as symbolic indicators of immigrants' commensurability with modern gender roles and other premises of modern liberal democracies. Their bodies are particularly important in the context of religious markers, such as head scarves, which have led to vigorous debates in several European countries, among them Germany" (p. 40). Their family life is also under scrutiny. As the author points out, the habitual belief widely spread among policy makers and, therefore, within the media discourse, is that the inability of Turkish women to achieve success in the German labor market is caused by their misogynist (Turkish) cultural background. But the most valuable and noteworthy part of Hinze’s research does not lie in the opinion of others. It rests in the individual voices of those who are usually silenced in the public debate, the Turkish women themselves. Drawing on the rich ethnographical material she collected, Hinze shows us that although Turkish women might share common experiences of rejection and discrimination, the process of ethno-national identity and cultural belonging is highly unique and individual. Through different personal stories, the reader gets a glimpse into what it means to be neither German nor Turkish. This ambiguous experience is nicely captured in a striking sentence by one of the respondents, Ceyda, who points out: "To be honest, I feel in the middle" (p. 90). This concept of “in-between-ness” is of course nothing new in the integration field. Many migrants have previously claimed that they feel like strangers both in the host country and also in the former homeland. But what makes their experience (and therefore the research) special is that they actually feel safe and secure in one place, and that is their local universe, their neighborhood. As Hinze sums up, "[w]hile in the larger German society (as in the larger Turkish society in Turkey), Turkish immigrant women and their in-between-ness stand out visually, in the immigrant neighborhood, they fit in" (p. 95). She also comes up with an interesting point on why Kreuzberg is perceived as more multicultural and welcoming neighborhood than Neukölln. In Kreuzberg, one can observe a vivid tradition of direct democracy, since many bottom-up policy solutions have been introduced there through the years as a result of immigrant activism. Lots of policy makers and civil rights advocates with immigrant background have grown up – both personally and professionally – in the area. On the other hand, Neukölln is far from being perceived as the center of spontaneous activism and civic networking. It is an example of top-down integration with dominant policy discourse where many projects have been (presumably in good will) introduced in order to increase immigrants’ employment. But instead of creating “second Kreuzberg”, Neukölln’s policy makers have built the image of controlled neighborhood and managed assimilation.

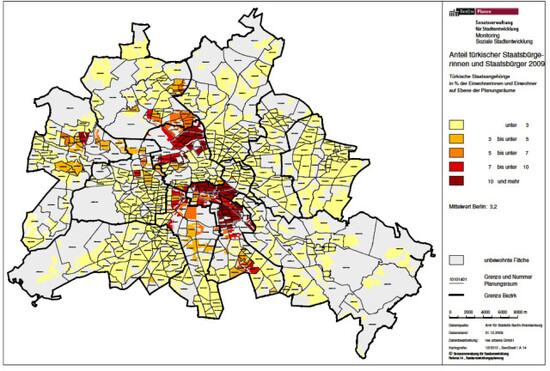

To sum up, Turkish Berlin represents a complex yet concrete and locally based probe into the current integration discourse of the most multicultural city in Germany. In the light of the recent rise of islamophobic tensions all over Europe and Pegida-marches in Germany, such a carefully elaborated study is all the more topical. Although it might sound like a cliché, the book has something for (almost) all. There is a historical overview of German integration discourse followed by the detailed analysis of how immigrants are perceived by Berlin policy makers for those who like to approach the issue from a broader and more theoretical perspective. For others, who tend to incline towards a more down-to-up and marginalized-actors perspective, there are the stories of Turkish women and their beloved neighborhoods. The book is also backed up by detailed graphs and tables for readers who demand precise and quantitative evidence. But there are also illustrative examples of advertisements or respondents’ “personal maps” that support the author’s arguments in a qualitative way. Nevertheless, the richness of the book is also its biggest weakness. Since Hinze is trying to capture the topic of integration in its complexity while including different points of view and various actors, the book is very dense and perhaps overly saturated. Moreover, the author’s endeavor not to left out any aspect of the intricate issue leads to a certain fragmentation and, at some points, the reader might feel that the different angles and points of view do not hold together properly, but sometimes rather fall apart. Yet, I consider the book very well written and – to a large extent – similar to the urban space in Kreuzberg and Neukölln. You don’t have to necessarily like every single corner in the neighborhood (there might be parts you want to avoid altogether), but it doesn’t mean you can’t admire it. This article has been funded from the project "Integration of Labour Migrants in the Czech Republic: Reinforcing the role of the Czech towns", CZ.1.04/5.1.01/77.00030, supported by the European Social Fund in the Czech Republic via the OP LZZ program.

This article has been funded from the project "Integration of Labour Migrants in the Czech Republic: Reinforcing the role of the Czech towns", CZ.1.04/5.1.01/77.00030, supported by the European Social Fund in the Czech Republic via the OP LZZ program.

Vanda Černohorská has studied Philosophy and Film Studies at Palacky University in Olomouc, Gender Studies at Charles University in Prague and Sociology at Masaryk University in Brno, where she continues her studies in the PhD program. She currently works at the Integration Centre Prague (ICP) as a branch manager in Prague 13. Earlier she had worked for two years at the Department of Asylum and Migration Policy of the Ministry of Interior.