Education and Higher Education for Third-Country International Students

Education: a benchmark for integration in the EU?

Education is high on the EU’s agenda. The governments of EU Member States set two overall education targets for Europe’s strategy for jobs and growth:

- Reducing early school leaving rates below 10% (from current 12.7%); and

- Raising the share of 30-34–year-olds completing third level education to 40% (from current 35.7%).

As EU member states have committed to achieving these goals by 2020, the strategy became known as Europe 2020.[1] In addition to the Europe 2020 goals, member states agreed to three additional education targets in the Strategic Framework for European Cooperation in Education and Training (known as ET 2020), which contains three additional education targets:

- Raising the average of adults that participate in lifelong learning to at least 15% (from current 9%)

- Reducing the share of low-achieving 15-year olds in reading, mathematics and science to less than 15% (no EU average exists at this point)

- Increasing the share of children between 4 years old and the age for starting compulsory primary-education participating in early childhood education to at least 95% (from current 93.2%).

If the EU is serious about meeting its education goals, education policies need to pay attention to the situation of immigrants and their children. Immigrants play an important role in achieving the overall EU education targets. For example, the overall EU rate for ‘early school leavers’ is 14.1% and the Europe 2020 target is 10%. The equivalent rate for foreigners is 30% and 33% for third-country nationals. Based on our own calculations using 2010 Eurostat data for the EU (data missing from Romania), if EU member states were able to close the gap for migrants, the EU ‘early school leavers’ rate would decrease by 1.3 percentage points. This would bring the EU 30% closer to its target.

Across all indicators, large persisting gaps between education outcomes of migrants in the EU and the general population confirm that improving the educational situation of immigrants is crucial in order to reach the Europe 2020 and ET 2020 targets. As a consequence, the 26 November 2009 Council Conclusions on the Education of children with an immigrant background invited the European Commission to monitor the achievement gap between native learners and learners with an immigrant background, using existing data and indicators. This is why EU targets in the field of education and training were used as the EU indicators for immigrant integration. During the Justice and Home Affairs Council on 3-4 June 2010, the member states invited the Commission to analyse these indicators, taking into account the national contexts, the background of diverse immigrant populations and different migration and integration policies of the member states.

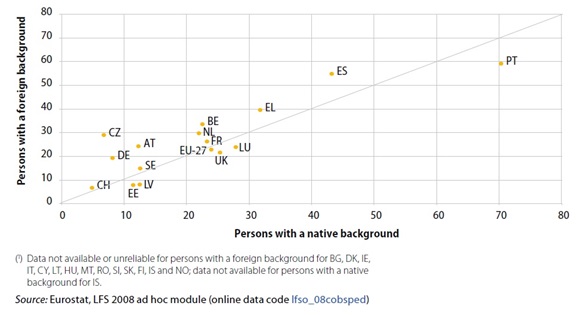

Highest educational attainment

First generation immigrants, especially non-EU migrants, are over-represented at the lowest educational level. At the high levels of educational achievement, the share of foreign-born persons (EU and non-EU) aged 20-64 is identical to the general population at EU level (24%). The differences between the two are more pronounced when looking only at persons with lower levels of education, where migrants are significantly more numerous among the low-educated population. This data does not specify whether the qualification was earned domestically or abroad—or whether a foreign qualification has been formally recognised in their country of residence. Therefore, this indicator for the first generation reflects both the performance of domestically-trained immigrants with qualifications from the country of residence as well as the educational background of foreign-trained immigrants with qualifications from the host countries. In many EU countries, considerable gaps remain for the second generation, i.e. persons with one or two immigrant parents. Compared to the first generation, there are smaller gaps for the second generation in terms of the proportion with a lower level of educational attainment. The graph below shows the rate of the low-educated population in the EU. Countries above the diagonal line have a disproportionate share of the second generation among the low-educated population compared to natives. The outliers are Luxembourg, Portugal, the United Kingdom, as well as the two Baltic states, Estonia and Latvia.

Rates of low education — comparison of second-generation migrants with a foreign background with persons with a native background (persons aged 25–54), 2008 (1) (%)

![]()

Early leavers from education and training

First and second generation children are generally at greater risk of exiting the education and training system without having obtained an upper secondary qualification. Early leavers from education and training are those students who have only achieved pre-primary, primary or lower secondary education. The early school leavers’ rate is lower for the second generation than the first generation, but still higher than the general population. At the EU level in 2008, the share of early school-leavers among the second generation was just four percentage points higher than the share among their peers with native-born parents.

Despite these many challenges, first and second generation students do not generally report low levels of positive learning characteristics. In the 2003 PISA survey, the OECD asked students to report their learning motivation, self-related beliefs, emotions, and student attitudes towards and perceptions of school. In fact, immigrant students often reported more positive learning characteristics than their native peers.

Factors associated with immigrant educational outcomes

Why do these differences remain between the first and second generation and the general population? A large and growing body of research is examining the factors that influence immigrant’s educational achievements. The differences in language spoken at home and socio-economic background (measured by income, field of occupation and highest educational level of parents) account for a large part of the performance gap between native and immigrant students. Even though socio-economic background explains a large share of the gap, still a person with an immigrant background has lower education outcomes in most EU countries compared to a native with the same socio-economic status. Other factors associated with a better educational performance for immigrant students include, for example, participation in early childhood education and care, early home reading activities, more hours for learning language at school, educational resources at home and a lower concentration in schools of students with a low socio-economic background. Another relevant factor is the years of schooling in the country of residence (measured by age of immigration). First-generation students who arrived in the country at a younger age outperform those who arrived when they were older.[2]

The general context also matters. Where the general population fares better, migrants generally also do better. As a general trend, the share of underachievers among immigrant pupils is higher in countries with more underachievers within the general population. The share of the foreign-born students with a university degree is higher in countries with more university graduates within the general population (e.g. Northwest Europe). Furthermore, more migrants leave school early in countries with a larger share of early school leavers within the general population (e.g. Southern Europe). This performance correlation implies that the general educational situation is a major factor for the general population, including for migrants.

Several studies show that students with an immigrant background tend to face the double challenge of coming from a disadvantaged background themselves and going to a school with a more disadvantaged profile (measured by the average socio-economic background of a school’s students) - both of which are negatively related with student performance. The impact of tracking – where students are grouped in different school tracks (levels) at different ages according to their abilities – is a vast debate among researchers. According to the OECD, almost all of the countries with large performance gaps between immigrants and native pupils tend to have greater differentiation in their school systems: for example, four or more school levels for 15-year-olds, such as lower, middle and advanced tracks. Many studies have found evidence that early division of students into tracks increases outcome gaps over time.

International Students: Recent Member State Policy Trends

International students are a growing immigrant population across the developed world and an attractive group as prospective immigrant workers. They are young, often highly educated with qualifications from the country, and sometimes fluent in the EU country’s language (depending on the language of their academic programme). Highly-skilled immigrants with language knowledge and qualifications from the country are often just as likely to find employment as the average highly-skilled person in the country. As a result, national policymakers and researchers often see generally positive impacts from international students, measured as major financial contributions through higher educational fees paid by third-country nationals compared to EU nationals, comparatively high employment rates upon graduation, and a low uptake of social or educational benefits due to their age and life circumstances. An increase in third-country national students rarely translates into greater competition for national or EU students for studies or jobs. Instead, the Commission argues that attracting third-country nationals to study and then work in the EU will increase the Union’s excellence in education and training as well as promote innovation, entrepreneurship, and economic growth.

Attracting international students is a recent policy trend in most EU member states. The full range of member states policies was surveyed in the 2012 European Migration Report on the Immigration of International Students in the EU. Potential international students are provided with information about the legal opportunities to study, work, and settle there. They are also provided with scholarships or funding, often through bilateral agreements with certain countries of origin. During their studies, international students in some countries have unlimited access to the labour market and self-employment, while others face restrictions in terms of sectors, labour market tests, and employer documentation requirements. After their studies, former international students can apply for work permits in the majority of member states, but often with restrictions based on the type of academic programme, type of employment, or, in the case of self-employment, access to investment and capital. Former students are rarely helped by their work experience during their studies, which are usually low-skilled jobs providing an additional income but not building their CVs or networks (e.g. student jobs).

International Students: Recent EU Policy Trends

EU cooperation on education aims to make the EU a global centre of excellence for higher education and training through greater exchange of information and best practice on higher education, bilateral agreements, and practitioner mobility programmes. In recent years, the EU has encouraged member states to approach the management of non-EU legal migration in terms of their labour market needs. This needs-based approach focuses – sometimes exclusively – on the need to attract highly-skilled workers, which draws policymakers’ attention to laws governing international study and research. The EU has prioritised the admission and retention of international students and researchers. For example, purpose-built European-wide portals have been designed for international students, called Study in Europe, and for researchers, called EURAXESS. Most importantly, the EU has adopted specific EU directives facilitating entry, residence, and mobility within the EU for students (called Directive 2004/114/EC) and for researchers (called Directive 2005/71/EC), as part of its sectoral approach to labour immigration. International students may also enjoy better opportunities to stay on and work in the EU after graduating, following implementation of the Blue Card Directive for highly qualified workers, depending on the national legal requirements. Additionally, EU mobility programmes, especially Erasmus Mundus, provide opportunities and simplify the administrative procedures for a small proportion of international students who are able to use these programmes. However, this proportion remains very small (1.4% of all new residence permits for the purpose of study in the EU in 2011).

Statistics: Small Numbers and Several Practical Obstacles

Nearly half of the world’s international students come now from Asia (especially China and India) and mostly head to the major study destinations: the US, UK, Australia, Germany, and France. These Eurostat statistics also show increasing but still rather limited numbers of third-country nationals entering the EU for studies, pupil exchanges, unremunerated training or voluntary service. [3] In 2011, the number reached 220,000, mostly in France (64,794), Spain (35,037), Italy (30,260), Germany (27,568), and the Netherlands (10,701). In that same year, only approximately 7,000 researchers entered the EU for research purposes, mostly in France (2,075), the Netherlands (1,616), Sweden (817), Finland (510), and Spain (447). Although the number of international students and interest in this group has significantly increased in the past decade, countries differ in whether or not international students are encouraged to stay and to stay in the country as temporary immigrant workers.

The staying intentions and barriers of international students were measured internationally for the first time by the Value Migration Project,[4] a collaboration by Migration Policy Group (MPG) and the Expert Council of German Foundations on Integration and Migration (SVR). The project surveyed over 6,200 international students at 25 universities in five countries – France, Germany, The Netherlands, Sweden, and the UK. The following summary of the findings may inspire debate in Central European countries about the possibilities to open more temporary work migration opportunities to international students. Almost two-thirds of survey respondents were interested to remain in their country of study for employment opportunities and the desire to gain international work experience, although permanent migration was not the intention of the vast majority of respondents. The international students with the greatest interest in staying tended to be younger, experienced working in the country, less likely to have children, more likely to study science- and technology-related fields (i.e. engineering, mathematics and natural sciences) and more often from countries in Asia and Eastern Europe (e.g. Ukraine and Serbia).

Comparing the survey results in the five countries with the official statistics on work permits, many more international students clearly want to stay than actually do in the end. One practical barrier is that most students did not feel well informed about the legal opportunities for obtaining a post-study work or residence visa. Since students were also reportedly more likely to leave due to family and personal relationships and concern about the insecurity of their legal status, facilitated access to family reunion for international students and long-term residence for former students may send positive signals. Moreover the report noted that former international students also face integration difficulties similar to other immigrants, including gaps in language proficiency, acculturation, discrimination, and concerns over their legal status. The report encourages states to develop ways to identify interested immigrant workers among international students and directly support their integration before and during their transition to the labour market.

The EU Future Education and Training Policy Debate

Given the increasing importance attached to international students and the limited action at EU level, the Commission judged that the aforementioned current EU directives on students and researchers (Directive 2004/114/EC and 2005/71/EC) are insufficient for attracting international students and researchers, given member states’ increasing interest in their policies on high-skilled immigration and the internationalisation of their national education systems. The Commission’s application report (COM 2011/587 final) regretted the limited potential of current EU rules, adopted under previous ‘unanimity rules’, leading to the weak level of harmonisation of member states’ needs and practice, and few legally binding provisions. Most notably, international students’ transition to employment is not regulated at EU level. The European Commission sees access to work at the end of the period of study as a ‘decisive factor’ in the students’ choice of their country of study.

A consultation with stakeholders was intended to guide the Commission’s revision of the Directives 2004/114/EC and 2005/71/EC. The exercise obtained responses from 1461 individuals/organisations (further details not provided). The only results published by the Commission were overwhelming support to improve the attractiveness of the EU as a destination for researchers, students, and, to some extent, for school pupils, volunteers, and unremunerated trainees. However these issues have not solicited great interest among EU-level NGOs on migration, which suggests that international students are not a major priority for their specialists working on migration and integration at national and local level.

The following shortcomings in the current Directives were selected by the European Commission in its proposal for a recast (COM 2013/151 final):- Vague/non-binding rules on admission and visa procedures, labour market access

- Severely restricted opportunities for intra-EU mobility

- Lengthy and variable procedures for admission

- Rules incoherent with existing EU funding programmes

- Several procedural obstacles faced by international student applicants (e.g. place of application, right of appeal)

- Covers au pairs and remunerated trainees

- Reserves the right to long-stay visa/residence permit for applicants satisfying all conditions for admission

- Gives 60-day time limits for decisions on visas/permit renewal

- Ensures procedural rights to a written decision and appeal in case of rejection of a visa/permit

- Establishes a benchmark that fees must be ‘proportionate’

- Increases information provision and transparency about the visa/permit process

- Establishes family reunion for researchers as more favourable in terms of admission, labour market access, and intra-EU mobility

- Simplifies intra-EU mobility for students and researchers, especially in EU-funded programmes (e.g. Erasmus Mundus/Marie Curie)

- Ensures greater rights for students to part-time work

- Reserves the right for researchers and students to search for work for up to 12 months after their programme.

The Commission ambitiously stated that the EU Council and Parliament will agree on the recast with a year or two in time for implementation by 2016.

________________________________________________________________________________

Questions for debate- In your country, what are the major barriers the first and second generation migrants are facing in gaining an access to university and higher education?

- Are university and higher education a priority for the major immigrant groups in your country? Why or why not?

- Are university and higher education explicit priorities in your country’s integration policy?

- How serious is your country about attracting and retaining international students? Are there major differences between EU internationals and third-country nationals?

- What similarities and differences do international students face in their admission to your country’s universities compared to other labour and family immigrants to your country?

- Do practitioners know about and use EU mobility opportunities for third-country students such as Erasmus Mundus?

- What reasons do international students give about why they do OR do not want to stay in your country? What barriers are faced by students who want to stay but cannot?

- Do international students receive sufficient language support and job-search support in order to find work at their level of qualifications? What practices could improve?

- Will the European Commission’s proposed recast (COM 2013/151 final) improve the situation?

- Are higher EU standards for international students something that NGOs and universities in your country are willing to fight for? Why or why not?

[1] To see these statistics today, go to the Eurostat website: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/

[2] For more on all these points, see www.migpolgroup.com/

[3] These EU statistics refer to only the 24 EU Member States covered by this directive, excluding Denmark, Ireland, and the United Kingdom. Croatia entered the EU on 1 July 2013.

[4] For more, see www.migpolgroup.com/

Thomas Huddleston is a policy analyst at Migration Policy Group, working on the Diversity & Integration Programme. His focus includes European and national integration policies and he is the Central Research Coordinator of the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX).