Death in the Life of Ukrainian labor migrants in Italy

у когось-похорон,

у когось – христини.

А тут час зупинивсь, і не поступає:

Ти-живеш, а життя – немає...

In Ukraine one counts minutes:

Someone has a funeral,

Someone has a baptism.

And here, the time stands still and wouldn’t move:

You live, but there is no life

Ольга Козак[i]

Death in the Life of Ukrainian labor migrants in Italy

For many migrants the time of their migration is measured by numerous events that happen at home in their absence: pictures of family and religious celebrations, marriages, the birth of new family members, and of course, the death of relatives and friends. While happy events may bring a sharp realization of time spent apart, it is really death that symbolizes the loss of time in migration, the impossibility of compensating for the separation.

The article explores migrants’ experience of death, focusing on its three major manifestations in the course of migration, i.e. the death of the person in care, the death of relatives and loved ones at home during the migrants’ absence; and finally, the death of labor migrants away from home. This text explores how death becomes a part of migrants’ labor experience, and how the symbolism and meaning of death changes with the death of the employers, the death of relatives back at home, or the incidence of migrant deaths in Italy.

Though a part of everyday life for many migrant care workers, death is rarely discussed in migration literature. Yet death provides a prism for migration that allows a deeper analysis of the everyday struggles of migrants. Through this prism one may consider the structural limitations of their position as labor migrants; the meaning of legality; the gender and socially determined opportunities available in migration. Raising the issue of death, as discussed in this article, will allow bring into focus the obstacles that make migrants’ transnational social fields uneven; it will also provide an opportunity to look into instances of ‘failed migration’, when the care-chains disintegrate or fail to provide an efficient structure for maintaining transnational life. This article also asks why death is so rarely discussed in migration studies, why it remains untouched in policy debates, and considers how the idea of death is seen as incompatible with the very project of labor migration.

In one of the few works on transnational migration focusing on death, Kat Gardner uses the prism of death and death rituals of migrants from Sylhet to London to explore the differential effect of migrant life on men and women (Gardner, 2002). The present article, however, focuses less on the ritual aspects of death, instead it takes a closer look at the structural limitations of migration. It considers the alarming effect of absences in the life of migrants and their families, and reveals the emotional price that migrants pay while establishing transnational care-chains and seeking to compensate for their own absences from home. Thus, discussing death in migration experiences highlights the effects of absences of care, and explores the individual burdens of care-chains. While focusing mainly on women’s experience, it is important to underline the gendered dimension; death becomes a predominantly female migration experience through women’s frequently more direct engagement in care-work for the sick and elderly, while e.g. male migrants, though exempt from the traumatic but everyday experience of death at work, occupy sectors of labor that put their health and life in more direct danger, i.e. working on construction sites and in other hard manual labor.

The article is based on research conducted for the PhD project in progress “Circular Migration of Two Generations: Ukrainian Migration to Italy.”[ii] The interviews and observations were carried out among migrants and migrant associations in several Italian cities (Bologna, Brescia, Ferrara, Milan, Naples and Rome), and among migrants’ non-migrating family members in the Western regions of Ukraine, between October 2007 and March 2008. For the purpose of this article a few UGCC officials were interviewed in both Italy and Ukraine, as well as some officials from the Ukrainian consulate in Milan, and members of Pieta, a pubic organization providing support for returned migrants, in Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine. [iii]

The death of the person in care: Nursing to death

According to the Caritas report 2007 there are 195.000 legalized Ukrainians in Italy, however, there are estimates that as many as 700 000 Ukrainians are working in Italy.[iv] The great majority of these people are involved in the care giving sector,[v] i.e. providing private care for the elderly, the sick, for entire families or children. Typically such work requires a care-worker’s 24-hour presence in the house, which makes most migrants choose live-in patterns of employment. Depending on their actual duties and responsibilities; their employers’ requirements; their legal status; and the individual agreements they make, such employment usually involves unregulated working hours and usually only allows for between two hours and two days of free time per week.

Working as a Caregiver.

Among the care work commonly undertaken by Ukrainian migrants, providing care for the elderly and terminally ill is considered to be the most difficult. It is a type of employment that demands a very specific type of caregiver; usually middle aged women or, less frequently, men. Younger women and men who have been excluded from this sector complain that Italians refuse to accept them in care work with elderly people because they do not trust young people with their parents and homes, believing that they would not be capable of taking care of the elderly. On the other hand, this is also the kind of job that young people usually try to avoid. Taras, 21, said that he would never voluntarily choose this work: “No, to wash and look after these old bodies? Please no! I am too young to do all that!”. Lida, 39, who currently looks after a three-year old and a one-year old child, originally provided care for an elderly person when she first arrived in Italy: “It’s so much better to work with children. Every day you see how they change, learn something new. When you work with the elderly it is regression every day. You feel like you regress every day along with them!”. Oksana, 25, remarks: “Have you seen what happens to our women who do that job?! They age twice as fast!” Therefore the most common profile of a Ukrainian caregiver is a 40-55-year old woman, who is married or divorced and often already a grandmother herself.

The stress caused by such care work is often both physically and emotionally intense. Ira’s (51) story is typical of many others in Italy. After arriving there with no knowledge of the language some 4 years ago, she ended up taking a job in a mountain village in the north of the country. As she arrived at her new place of work, she heard screams and the sounds of a struggle coming from the flat: “My employer opened the door and I saw an old woman fighting with her daughter. When they saw me they stopped, but the old woman was so difficult…she wouldn’t sleep for a minute, I had to be beside her all the time. The children treated me nicely and tried to teach me some of the language, but after a whole day of work and all those sleepless nights next to ‘my granny’ things just wouldn’t stick in my head. I had a 2-hour break each day and one day off per week, but I had no place to go and for about two months I knew no one. So I found a spot by the river, where I would always go. I had my routine there; everyday I would cry for 30 minutes; study Italian for another 30 minutes; sing for the remaining 30 minutes; and go back to my work. This is how I saved myself from insanity. My employer thought I would run away, but where would I run to with no money, no ticket, and not knowing the language?” Ira stayed in this job for a year and three months. In Ukraine Ira worked as an economist. When asked if she was trained to provide the medical care she was expected to give to the elderly woman, Ira gives an answer that is repeated by many migrant women in her position: “ I have learnt everything at work – to give injections, massages, everything. I had no choice but to learn; I arrived in February and it was awful to stay in the park all day, in the rain and the wind, waiting for a job. I had to leave the place where I was staying every morning at 7am and then I spent the whole day outside, hoping that someone will come up with a job. I took the first one they offered me.”

Though some migrants have previous experience of caring for their own elderly parents – some of whom may remain in a critical state back in Ukraine – for many of the migrants this lack of familiarity with the medical side of their work, the necessity of intimate contact with a sick and aged person, is a major shock and may lead to traumas. Tania, 49, who used to work as a technologist at a large plant, left Ukraine to earn money so that she could afford good medical care for her grandchild. She ended up getting her first job only a month after her arrival in Italy. "They told me that it would be a job in a mountain village, and I had to pay 100 US $ for it. I said I don’t care, as long as it is a job; I was so cold and exhausted from walking all day long through all these churches and parks in search of jobs. So an Italian man came and picked me up, and as I was trying hard to learn Italian during these months I understood that I would work caring for his mother. The day we arrived at his home I prepared dinner for them, and since the ‘granny’ was lying in bed I didn’t really see her. Only in the evening did I realize that she only had one arm and one leg. My heart sank! I started crying and crying but I couldn’t refuse the job. It was a nightmare job; the ‘granny’ could neither speak nor see and I had to lift her up from the bed, put her into the wheel chair, take her to the bathroom and wash her every day. I had to put her on the toilet, pick her up, and change her diapers. I just cried and cried all day. I did not have to cook food, just to clean and to feed ‘my granny’, but I couldn’t swallow even a piece of food for myself. I tried but I couldn’t. Finally, on the 7th day I dropped the ‘granny’ on the floor and she was so heavy and I was trying so hard to pull her up that my hemorrhoids protruded. My employer came and saw me crying and that’s when I told him I couldn’t deal with this any more. I begged him to take me back to Caritas where he picked me up.” Her employer sympathized with Tania and found her the next job; she was to look after his friend’s mother, a woman with terminal cancer. From that time Tania has never really been out of work; she moved from job to job on her employers’ recommendations, and even helped her husband to come over to Italy as well.

On top of the exhaustion that comes with providing care for a terminally ill person, and the fatigue of the final days of care, the actual death of the person in care often means the end of the employment for the migrant. Lida, 39, for instance, recalls one of her contracts clearly stating that she would remain in the house only as long as the employer’s mother was still alive: “It was a fair contract because it was hard for the man to maintain a huge flat and three people as house workers. We had a deal from the start that once his mother passed away I would have to go.” Due to the uncertainties that come with unemployment, the death of the employer fades away in relation to one’s own gloomy perspective searching for a new job, new accommodation and employers. Ira (mentioned earlier in the text), spoke to me only one week after she had buried her seniora. Ira had a close relationship with the woman who passed away, as well as with her family, however, her mourning could not last longer than a few days, as the employer – in accordance with Italian employment regulations – is only required to keep the care worker in his/her home and pay a full salary for two weeks after the end of the contract. Therefore, though grieving over the death of the person who had treated her so nicely, Ira was forced to look for new accommodation and a job; she had to visit potential employers and appear cheerful and smiley, so that they would want to hire her.

The Cost of Legalization

Legalization, i.e. receiving an Italian residence permit, remains the ultimate goal of migrant Ukrainians. The permit allows a migrant to become “transnational,” i.e. to go home for vacations or in cases of emergency and then to return to Italy. Most of the interviewees admitted that they had to stay in Italy for 2-5 years before they became legalized and could make their first trip home. One of the few ways that Ukrainians can become legalized in Italy are so called sanatoria, reunification of the family, and Decreto Flussi. Sanatoria allowed for the legalization of all migrants present and working in Italy with valid contracts and residence, but it happened only once, in 2002-2003. Reunification of the family requires one member of the immediate family to already be legalized. The most common way to become legalized is the so-called Decreto Flussi; designed to meet demand for foreign labor, the regulation requires an Italian employer to send a request for a specific employee that is living abroad. This can only be done during the period of Decreto Flussi, and with a contract for that particular worker. While it was designed to bring foreign labor into the country, for years (2003-2007) the regulation served to legalize illegal workers who were already working with Italian families.

Ira’s situation was in many ways rather advantageous. Firstly, she had a residence permit in Italy and therefore did not have to depend on a family to apply for her legalization, though she was required to find an employer by the time her one-year residence permit expired. Furthermore, she had been in Italy long enough to build up a sufficient number of contacts and recommendations, and therefore she did not have to pay for the services of employment intermediaries. The situation of those migrants without permits is much more complicated; they must find a family that is willing to start the process of legalization and to pay their taxes. It is common for migrants to agree to work for less money or in harsher living conditions in return for the employer’s help with legalization. In the case of the sudden death of the person for whom they provided care, migrants often risk being left without a legal status, their months of sacrifice and time spent in Italy wasted as they remain no closer to legalization and thus to the opportunity to visit home.

The Cost of the Job

Since many jobs are ‘sold’ even when passed on from one relative to another, the quick death of an employer can also mean a serious financial burden. In the northern part of Italy, depending on the employer’s family and the working conditions, a job can cost from 250-400 €. This money must be paid by the migrant to the previous employee or to an intermediary who recommends the family. It is common for this money to be paid during the first few days of employment; thus it becomes a practical concern for a migrant to ensure that they are not sold a job with a person in care who is about to pass away. The worst case scenario for a migrant would be when they start a job, pay their dues and then have to move on within a few weeks because of the death of their employee. In this way some women can lose several employers per year. Kateryna, 47 who is currently unemployed after three years in Italy, regrets ever having come: “Italy hasn’t been good for me. I am simply very unlucky. I had good jobs, but I was just so unlucky that they all would die on me…Last year I “buried” three employers, what could I do? And to get some of these jobs I had to pay!”

Although such practical concerns, and the fear of unemployment, mean that death must be calculated as a cost to the migrant, this perspective will usually be supplanted when a migrant gains a job and begins to develop an emotional connection to the person in care. Thus, Ihor, 27, once an economist with a University degree, came to Italy to work as a live-in badante for a bedridden Italian man, who died after several months: “I couldn’t believe the old man would die on me… I did everything to keep him going and when he finally passed away I cried…cried not so much for him, but for the fact that I will have to leave this family, which I felt was my home now. But I had to move on…”

These ties, and the position of the migrant as a domestic live-in worker, create a complicated mixture of simultaneous closeness and separation; of dependency and empowerment of the migrant. Sofia, 52, has been providing care for an elderly couple in a small town in Northern Italy for 5 years, remembers how after the death of the senior, his wife started treating Sofia with much more respect. Sofia explained, “Though my seniora has children, she finally realized that I am the only one who can really care for her. Her children have their own lives, and she would be completely alone if it wasn’t for me. She knows that she can rely on me, because I also depend on her; I need money, she needs my care (laughs). We need each other in this way, and though it sounds pragmatic, she knows that it’s a reliable connection and that she can trust me.”

Indeed, during the last and most difficult months and weeks of their relatives’ illness, many families rely on caregivers to release the pressure on their own families and lessen their personal pain. Thus, Tania reminisces about her seniora’s last few days of suffering from cancer: “I realized those were her last days because she had really lost her mind. She was talking nonsense and refused to take her medicine any more. During one of the last days she started throwing things at me and shouted “Vai via putana russa!”[vi]. I knew then that she was not herself anymore. I didn’t know what to do; all her family, all her children, were out of town at the seaside. I was afraid to call them, to bother them, but luckily seniora’s friend stopped by and when she saw seniora in such a condition she told me to call the family and ask them to come back. My seniora was in a coma then, but I still had to care for her, to wash and turn her over for three more weeks while she suffered and finally passed away.”

This interdependency and pressure can cause emotional difficulties, leading to severe stress and traumas that are often suppressed, as the migrants have to move on and get new employment. In fact, while there is little research done on how these stress factors affect a migrants’ own health,[vii] the caregivers often refer to their work and employers as “eating up” their health, youth and energy. One of the migrants, Vira, 49, who worked as a theatre director in Ukraine, has learnt that she had cancer and is now recovering after two operations and a course of chemical treatment. While talking about how she discovered her illness in Italy, Ira recalls that her very first job in Italy five years ago had been to provide care for an Italian seniora who also had a cancer. Vira explains, “now I remember there is a belief in Ukraine that when old people die one shouldn’t hold their hand, as they can pass all sorts of bad energy onto you. I didn’t know it back then. When my seniora was dying I felt so sorry for her, as we had become so close, that I was the only one who was beside her deathbed. She grabbed my hand and held it so tightly as she was passing away. These days I sometimes recall that day; maybe people are right saying that it’s better to stay away from a dying person? Maybe she did pass her disease on to me somehow?” Like many others, Vira had no time to recover from the stress of caring for a terminally ill person, and had to move on to another job. After illegally staying in Italy for 5 years, with no chance of visiting home, Vira has finally got her first residence permit due to her own illness, and not because any of her employers agreed to legalize her. The permit allows Vira to consider her first trip home or the possibility of her daughter visiting to Italy.

The death of the person in care highlights a complex network of emotional and economic dependencies that mark Ukrainian migrants’ lives. For those who have not dealt with death before, or who have not seen it in such close proximity, this experience becomes one more shock amongst the others experienced in the move to a different country and starting to work in an unfamiliar environment. The intensity of the work, the dependency of the employer, and the level of intimacy required of the care provider erase the conventional distance between migrants and employers, otherwise maintained so willingly. On the other hand, the migrant remains highly dependent on her employers. This is true not only in the case of money, but also for initializing legalization, which would allow migrants to move freely across the borders and visit home. This makes migrants highly vulnerable to their employers’ demands, which often increase during those last, most difficult months and weeks of the illness. Often, these demands become so soaring that despite the attachment that the migrant might have developed to the employer, their death is a liberation from the unbearably harsh working and living conditions. Moreover, the necessity to immediately search for a new job and home serves to remind the migrant that no matter how much care and personal emotion s/he has invested in the work, s/he can never be a part of the family and remains a paid employee. Such conditions often lead to a certain commodification of the experience, as the death of the employer comes to represent a mere loss of job, thus encouraging the migrant to be pragmatic about the stressful experience of witnessing and being so intimate with death.

Death at home: Symbolic of all losses

Unlike the death of a person in care, which is an expected disruption in the migrants’ experience, the death of relatives and loved ones at home is usually seen as a tragedy that represents all the losses that take place in the course of migration.

One such loss is brought on by structural restrictions, by migrants’ inability to move freely between home and Italy and their need to stay in Italy as long as it takes to obtain a residence permit. This is often equalized with the loss of freedom; actual enslavement; and submission to the fate that pushed a migrant to leave in the first place. Migration thus becomes a structural prison, a form of exile in the most literal sense of the word. Sofia (mentioned in the text earlier) returned home for the first time a few years ago because she knew that her mother was dying: “I had spent four days on the road. Four days! It was in December, it was so cold and they kept us for hours and hours at every border. My mom knew I was coming but she couldn’t wait for me and finally passed away. I arrived on Tuesday morning and she had passed away on Monday night!” Sofia’s voice breaks as she repeats what sounds like a chant she has gone over many times through all these years: “I ask myself, mom, why did it have to be like that? I was on the phone with her and I kept telling her “Mom, dear, wait for me, I will come to see you,” and she replied, “Daughter, I’ll be waiting for you!” She knew I was already crossing the Ukrainian border. But I was only in time to see the coffin.”

Such losses, especially the loss of parents, are particularly painful as migrants often leave their own elderly parents in order to provide care for similarly aged Italians. In the cases of two of my interviewees – Olha and Hanna – their mothers died within a few months of their departure for Italy. Unable to come back for the funeral due to their illegal status in Italy, both Olha and Hanna feel incredible guilt, believing that they have neglected their daughters’ duty by placing material benefits above their families. Many years after the death of their mothers both are still on the verge of crying when they remember this loss. In fact, Hanna feels that to a certain extent her migration project was a failure because her mother could not enjoy the benefits of it: “I only wish that my mom lived a little longer to be able to enjoy the relief that the money I sent back home has brought. After she spent all her life scrutinizing all her needs to give my sons proper food and clothing, I so much wanted her to be able to buy as much meat or fruit as she wanted, all with the money that I have sent from Italy.”

Such feelings, unfortunately, closely correspond with the public shaming discourse of female migration from Ukraine. Women who leave their home are often seen as neglecting their most fundamental duty to keep the family intact. For instance, a Greek Catholic priest in a Ukrainian village has remarked to me in an unofficial interview that while he has seen many instances of migration, those families in which men migrate usually do much better than those where women leave: “The men are more reliable. Wherever there is a woman who has left, that household rarely enjoys any benefit. The women need to stay at home, otherwise everything just falls to pieces.” Despite such a statement, my interviewee from the same village seem to manage her Ukrainian household from Italy with success; she bought a new flat in the neighboring town, helped her elder son to set up a business and celebrate his wedding, and managed to re-unite her two younger kids with her in Italy, all within 7 years of migration.

Oksana Pronyuk, one of the initiators of the association providing social and psychological support for returned migrants, gives full credit to migrant women’s major contribution to their families, and the local and Ukrainian national economy. Yet she also emphasizes again and again that female migration has become a tragedy on a national scale. She notes that since the former president of Ukraine, Kuchma, called all Ukrainian women in migration “whores” in early 2000, many women have had to deal not only with the hardship of migration but also with the burden of suspicion and shame from their families in Ukraine. While recognizing the unfairness of such double pressure, and campaigning to force Kuchma to apologize publicly for such a statement, Oksana calls for the return of all women to their families in Ukraine: “Mothers should not leave to earn money. Men can leave, but not mothers. What is a family without a mother? What kind of childhood can a child have without a mother? Ukraine will have to face the consequences of this migration years from now, when all those children who are now separated from their mothers will grow up.” In her pained comment, however, Oksana makes no effort to make men more accountable for doing a full-time care work inside the family.

In many respects deaths at home are the ultimate migration trauma: a symbol of all the losses that take place during migration, and often perceived as a punishment for prioritizing material considerations over familial relationships. While marriages and the birth of grandchildren can inspire a painful sense of separation, the death of loved ones reminds the migrant of the impossibility of regaining the time spent away from home.

Death of a migrant: the Return

The least considered aspect of death by both migration literature and migrants themselves is probably the possibility of the migrants’ own death in the course of their stay abroad. Two rather shocking factors testify to how little concern is given by migrants to the possibility of such an outcome of their migratory experience: one being the absence of any unified mechanism of transporting the bodies in case of migrants’ death back to Ukraine, and secondly, the lack of any form of private insurance or protection from incidents and possible death during migration.

Thus while the unofficial estimate of Ukrainians in Italy is as high as seven hundred thousand, there are absolutely no arrangements in place for taking care of the deceased. The three existing Ukrainian Consulates in Italy (Rome, Milan, and Naples) do not have proper funds to cover the expense of transporting bodies back to Ukraine, costs which range from 2000 Euro by land and 8000 Euro by air. In 2005 the Ukrainian Embassy had a fund of 72 000 Euro set aside for cases of death, but the number of registered deaths of Ukrainians in Italy was as high as 182 in that year.

Raising money

In the absence of infrastructure for dealing with repatriation, a common pattern has emerged: the cost of transportation falls on the shoulders of the family of the deceased. If they cannot provide the money, then donations from various sources may be collected. While the Consulates usually have a small amount of money that they can contribute in such cases, their role is largely representative rather than financial; they are informed whenever a death of a Ukrainian citizen is registered, and they sometimes take the burden of informing the relatives or assume the administrative task of issuing the necessary permits for the transportation of the body. The bulk of the financial contributions usually comes from the church; most often it is the UGCC that plays a particularly central role, as it remains the most numerous and active Ukrainian church in Italy[viii]. The church may also provide a special mass for the deceased; help to organize the wake; and raise funds among churchgoers.

Another generous contributor may be the migrant’s most recent employer, who is not legally obliged to provide any help. If the migrant has a permit and has paid taxes and made other social contributions, s/he can expect the same financial contribution from the state in the case of his/her death as when he / she loses a job. If the collected funds are not sufficient to cover the transportation expenses, then collecting money in places where Ukrainian migrants usually gather to spend time between jobs, i.e. in parks. Ukrainian mini bus parking lots, and Sunday bazaars becomes another option. In smaller towns, news is passed on by word of mouth; in bigger cities, like Naples, it is possible to see relatives or friends of the deceased standing in the crowded Ukrainian week-end bazaars or walking through the parks approaching people and collecting money.

In the event of death

Tamara, 47, a migrant living in a northern Italian town, is the head of a Ukrainian association which was founded some 8 years ago. It helps migrants with legal issues, represents Ukrainian interests on the municipal level, and organizes cultural events. In this particular town their association took the responsibility of sending home the body of a Ukrainian woman found dead in a park. To collect the 2000 € that the Italian funeral agency quoted for the transportation of the remains, Tamara asked for the support of the town UGC church community and collected 1000 € in church donations. She also asked for help from the poverty office in the town municipality and the local migration office. Finally, she was able to strike an agreement with the municipality, which made it possible to cremate the body for only 400 € instead of 2000 €. Tamara explained the long-term benefits of such an agreement: “We’ll cremate her as soon as we get permission from the Ukrainian Consulate. Then we’ll ask someone who is going to Ukraine to put the urn with the ashes into their luggage… they won’t say ‘no.’ We will send some 100 € or more to the daughter of the deceased, as a small support, and the rest of the money will be left in the fund so that when similar case happens, we will have the initial resources to help.”

Though not authorized by any officials to organize these processes of repatriation, Tamara has had to deal with many similar cases since she started in 2003. Now she continues to argue for the creation of a special fund, which would be connected to the church and would provide public reports on its expenditure. Tamara argues that it is crucial for such a fund to be associated with the church, as migrants would not accept an independent initiative, suspecting that it was setup for individual benefit. On top of that, the church is the largest single organization that brings Ukrainian migrants together in Italy. However, all of Tamara’s attempts to create such a fund have failed for years now: “People don’t take the possibility of death seriously; it’s only when they hear that someone has died again that everyone is stricken with a sense of personal weakness and they get really scared and donate a lot. However, it is impossible to convince people to contribute a small amount to a fund in advance! How would one even go about this? Should one just go to the park and say: ‘Please donate some money which we can then use in case of your death!’ This would not take us far!”

Natalia (47), a migrant working in a southern Italian city, has undergone surgery for cancer, and now volunteers for the Italian migration office in her town. She is looking for a job as a cultural intermediary in a hospital. She is similarly concerned by the lack of migrants’ initiative in protecting themselves in case of emergencies or death: “I am not even mentioning insurance or something. I am simply telling them: ‘Women, have respect for yourselves! Don’t send every cent back home! You have to have your own savings, no matter how much you trust your husbands or your children! When you have those savings and something happens to you, you can pay for yourself without making your families pay for you.’ But no, so many women send home literally everything, leaving themselves just enough money to buy food.”

Due to the lack of infrastructure, as well as the lack of migrants’ own resources, the death of a migrant is not only a major emotional trauma for the family but also a serious economic blow. Therefore, migrants often are forced to be pragmatic. Halyna (60 and a mother of 4 children) has a ‘record’ of having arranged the transportation of several coffins back to Ukraine. To do this she collected money in church, in the parks, everywhere she could. She has arranged this with no official sanction, volunteering her time and energy. She also collected money for the terminally ill, in order to either save money for the transfer of their remains after death or to pay someone to transport the dying person back to their home.

Natalia has also accompanied a terminally sick cancer patient on a mini bus trio back to her relatives in Ukraine. Natalia comments: “We have to be practical about these issues; when a family is about to lose a breadwinner, it makes a difference whether they will pay 100 € for a bus ride, or 2500 € for the transportation of the remains.” On the other hand, Natalia notes that they have to be very careful not to have a negative impact on sick people. A woman she has known for a while now is at a terminal stage of cancer, however, the doctors have not informed the patient how critical her state is. Natalia feels she is in an impossible situation: “The doctors tell me she is in a bad shape and that I should ask her to go home. But how can I say this to her?! Once she hears it she knows it’s all over for her and this will just break her. I can’t tell her to go home until she herself decides or until after the next surgery, when the moment is right.”

Alongside all these practical issues, there is an important symbolic aspect that should not be overlooked: the necessity of the return of the migrant to her / his home. Tamara, who helped to send home the remains of a woman found in a park, was particularly appalled by the fact that the Italian municipality did not report this death to the Ukrainian Consulate. Instead, the municipality wanted to bury the woman as if she were a local poor person and at their expense. Tamara has some clear objections to this: the difference between the length of maintaining the grave (in this case it would be 10 years in Italy, while in Ukraine, it is either unlimited or 90 years), and the anonymity of the burial. Tamara is mostly disgusted by the idea of the ‘unknown’ grave of a Ukrainian migrant: “This would be barbarism on our part to let one of our women be buried here. We know that in 10-12 years the grave will be emptied and someone else will be buried there. This goes against our Ukrainian customs. And after all, this woman has some family in Ukraine, don’t they deserve to have a grave for their mother, where they can come and mourn her properly and take care of the grave? So we try not to abandon these people, not to bury them here. They at least deserve the right to come home and have a proper grave.”

Talking of migrants’ death, thus, involves a complex intertwining of materialistic and symbolic manifestations. On the material level, it is a matter of saving the family of the deceased from a major financial burden, temporality of grave in Italy, lack of possibilities for families to look after the grave. Symbolically, death undermines the very temporary aspect of labor migration and possibility of reunification, even if through a practical and ritualistic care after the grave. Finally, death in migration threatens with turning a migrant into an “unknown grave,” internalizing the absence, which temporarily already exists in migrants’ families. Therefore the return from migration, even if only the return of the body, is crucial.

Conclusions

Looking at death as a part of the labor migration experience brings a number of symbolic and material aspects of migration into focus. There is a contrast between the effects of different deaths on the migration experience. On the one hand, the death of employers can lead to a trivialization of death: as an unavoidable part of their work experience, migrants are cautious to not get too emotionally involved. The time that a migrant has to deal with the emotional experience of death is limited by the necessity of moving on. Thus the significance of the employer’s death fades in the light of imminent job insecurity, or a loss of the legalization prospects and the corresponding economic losses that may occur. The death of labor migrants themselves is also trivialized but in a different way; it is unimaginable for the migrant because it goes against the whole labor migration project that involves hard work, restriction and separation, all endured for the sake of return and a better life together with the family in the future. It is all for this moment of return that a migrant puts his/her life “on hold” during migration. In other words, if the death of the migrant could be conceived of as a possibility, the migration project would no longer be considered as worthwhile. Finally, it is the death of relatives at home that gains the most significance; on a symbolic level it often becomes a locus for all the losses that take place during migration; the loss of time, of family experience and intimacy, health and youth amongst other things.

Barely discussed in migration studies, death affects many aspects of a migrant’s life: be it structural opportunities for legalization, a source of economic fraud, a burden of failing to perform one’s family duty, or a symbol of both separation from and return to home. Death, which itself stands in opposition to the labor migration project, highlights the painful impossibility of overcoming the absences; the emotional inefficiencies of the care-chains; and the emotional price paid by the individual.

The article is a part of the project "Czech Made?" realized by the Multicultural Centre Prague and supported by the European Commission.

Reference List

Gardner, Katy. 1998. “Death, burial and bereavement amongst Bengali Muslim in Tower Hamlets, east London”, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 24, 507-23 pp.

Gardner, Katy. 2002. “Death of a migrant: transnational death rituals and gender among British Sylhetis”, Global Networks 2, 3 (2002), 191-204 pp.

[i] Dumky. Piccole Ballade: Pensieri in forma poetica di donne ukcraine. [Versed thoughts by Ukrainian women]. Olha Vdovychenko ed. Editrice la Rosa. 2003.

[ii] The PhD project is carried out with the Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology at the Central European University, Budapest, and with the financial support of the Marie Curie SocAnth Fellowship.

[iii] Realizing the highly private nature of this topic, I have decided to change all the names, even though many interviewees were fine with using their names for the research. Also due to maintaining better privacy, and because my research have not indicated any significant regional differences, the names of the towns and cities were also omitted.

[iv] “For the Second Time Italy Legalises Our Labour Migrants.” Express, Lviv. (June 19th 2006), http://www.expres.ua/articles/2006/06/19/8869/ (accessed Dec. 18 2006).

[v] According to Caritas reports of 2003 64.1 % of Ukrainians in Italy are employed in taking care of the sick and elderly, 6.4% look after children in Italian families, 18.5 % are housekeepers in Italian homes.

[vi] “Get out, Russian whore!”

[vii] See Diploma work of Yevheniya Baranova at Universita Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (2006-2007). Yevheniya, a gynecologist doctor in Ukraine, after 10 years of working as a badante in Brescia defended a degree in medical college, writing about the psychological and health problems of East European care workers in Italy. (Title: Problematiche della salute delle donne immigrate provenienti dall’Europa dell’Est. Utilizzo del Sistema Sanitario Nazionale e ruolo dell’infermiere nell’assistenza e nella formazione.)

[viii] There were 114 UGCC in spring 2006 and their number is still growing.

Images:

Visiting the grave of the previous employer.

Afternoon coffee.

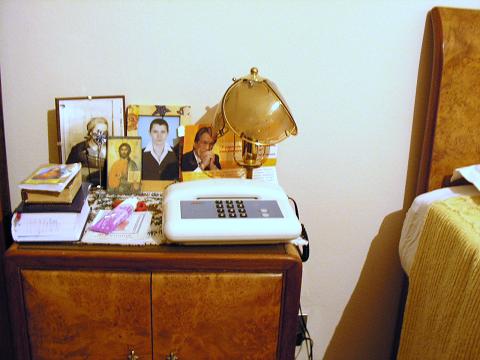

On the night table of a domestic live-in caregiver a picture of the deceased mother, an icon, a picture of her son, and Ukrainian president.

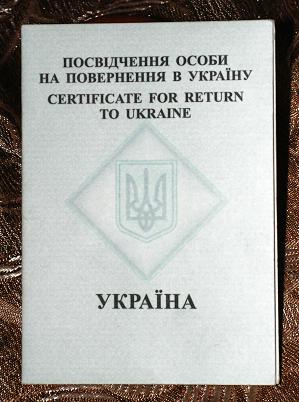

“Certificate for return to Ukraine,” a paper used for a short time by some embassies after the Orange Revolution, allowing migrants who stayed in the countries of the EU illegally to go back to Ukraine without a record being made in their actual passports.

Olena Fedyuk is currently working on her PhD dissertation on Ukrainian labor migration to Italy at the Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology (Central European University, Budapest). She was born an grew up in Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine, and holds her MAs from the University of Kansas, USA (Indigenous Nation Studies program) and CEU, Hungary (Nationalism Studies). Her academic interests include legitimacy of border, ideas of belonging, various forms and manifestations of nationalisms, pop culture and media studies.