Circular Migration and Development: An Asia-Pacific Perspective

There is a growing international discourse on migration and development and especially the potential for international migration to deliver development dividends to low income origin countries. One element in this discussion has been the argument that circular migration tends to be more effective in delivering these positive effects than permanent migration. It is considered that circular migrants have a stronger commitment to their origins than permanent migrants, send a greater proportion of their income in remittances and are more likely to use their training and experience to work in the origin country. Thus some advocate the encouragement of circular migration from low income to high income countries in preference to permanent settlement. Others, however, point to the problems historically with circular labour migration schemes which have involved exploitation of the migrants involved and produced limited benefits to home areas.

The polarisation of debate on circular migration is unfortunate since it is the author’s experience that in fact both sides of the argument can produce strong empirical support. In some contexts circular migration is a preferred migration strategy and does deliver development dividends while in others there are negative outcomes. The argument should not be couched in terms of whether or not circular migration has positive impacts. It should rather be around under what circumstances can it produce a positive outcome? What policies and opportunities are needed to maximise the development dividend but also to reduce the chances of negative outcomes?

The presentation goes on to examine some examples of the extent and nature of circular migration in the Asia-Pacific region where it is the dominant mode of labour migration. From the extant research a number of principles are advanced which may indicate best practice in the development of ‘development friendly’ circular migration. While the empirical evidence remains limited it is argued that widening demographic and economic differentials in the region, together with a range of other forces, ensure that there will be more, rather than less, migration from low income to high income countries. Maximising the positive development impacts of this flow does not mean advocating circular migration or permanent migration. What is required is a judicious mix of types of migration which are best suited to the contexts and needs of origin and destination countries and those of the migrants themselves. However, that mix needs to be developed in a quite different cultural context than is often the case at present. For development dividends to be delivered destination countries need to consider development impacts of migration among the elements they feed into the migration policy decision making process. Evolution of ‘development friendly’ migration policy does not necessitate jettisoning the sovereignty and interest of destinations but it does involve cooperation with, and considering the impacts upon, sending countries.INTRODUCTION

The year 2010 is a significant one from a demographic perspective. It marks a significant watershed because in the world’s high income countries the numbers of people in the workforce ages (15-64) will begin to decline. The World Bank (2006) projects that while there will be considerable intercountry variation as a whole high income economies will suffer a net decline of 25 million working age people by 2025. At the same time there will be an increase of 1 billion working age people in low income countries. The appreciation of this increasingly steep demographic gradient has been a growing recognition that it will add to what is already a significant migration from south to north countries (United Nations 2006). However there is a growing debate regarding the form that migration will or should take – permanent displacement or circulation. It is this issue which this paper takes up. It begins with a discussion on conceptualisations of circular migration. It then looks at the contemporary debate on circular migration and examines the arguments which have been put forward in support of and against the encouragement of circular migration. It then makes an assessment of the circular migration literature in an attempt to assess its potential role in the development in origin communities. In doing this it draws not only on that concerned with temporary international migration but a much more longstanding body of work on circular migration within countries. The first section draws out some policy implications of the findings. The argument presented is that circular migration does in fact have the potential to contribute positively to economic development in origin communities but that hitherto this impact has been diluted by poor governance within circular migration institutions and structures. It is suggested that there needs to be a judicious mix of carefully derived and well managed permanent and circular migration alternatives available to south-north migrants if triple bottom line win-win-win outcomes are to be achieved for migrants, their destinations and their origins.

CONCEPTUALISING CIRCULAR MIGRATION

Zelinsky (1971: 225-26) makes the distinction between conventional migration as ‘any permanent or semi-permanent change of residence’ and circulation as ‘a great variety of movements, usually short term, repetitive or cyclical in nature, but all having the lack of any declared intention of a permanent or long lasting change in residence’. However as with other dichotomies in migration (King 2002) there is a considerable blurring and overlap between permanent migration and circular migration. This overlap can take several forms as can be illustrated in the Australian context where arrivals in the country are required to state their intentions as to whether they intend to stay in Australia permanently as a settler, on a long term basis (for more than a year but they intend to return to their home country) or short term (intend staying less than a year). The blurring of permanent and circular is evident in:

Among immigrants who have settled permanently in Australia in the postwar period more than a fifth have subsequently left (Hugo 1994; Hugo, Rudd and Harris 2001), a fact that can be established since Australia collects data on emigration as well as immigration.

Currently in Australia (2007-08) 27.5 percent of the permanent additions to the population through migration are migrants who entered the country on a temporary visa but have applied for, and obtained, permanent residence or citizenship (DIAC 2008).

Despite this overlap it is possible to identify circular migration as a distinct type of mobility which is characterised by a pattern of coming and going between a ‘home’ place and a destination place. It is differentiated from commuting by the fact that the circular migrant needs to stay away from the home place for longer than a day. One internal migration study found the frequency of circulation is influenced by the distance between home and destination, the cost of travel, the nature of work at the destination and cultural factors (Hugo 1978). That study in Indonesia found that patterns of circular migration vary from weekly to absences of a number of weeks to annual or biannual returns when the workplace was a distant island of the Indonesian archipelago. For international migration the absences are likely to be greater but in cases where the home place is near a border the pattern of circulation can be more frequent. The latter is the case, for example, for migrant workers from Southern Thailand working in northern Malaysia (Klanarong 2003).

Another key distinction to be made is between circular migration and temporary migration. While the latter includes all forms of non-permanent movements the former is the subset which involves return, repetitive and cyclic patterns with a continuing pattern of mobility between origin and destination. Newland, Agunias and Terrazor (2008: 45) have characterised the international version of circular migration as a ‘continuing, long term and fluid movement of people among countries that occupy what is now increasingly recognised as a single social space’.

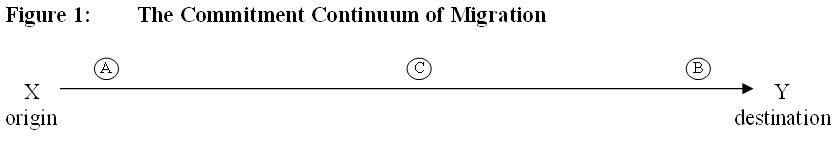

While conceptually it is possible to make a clear distinction between permanent and circular migration it is not as clear-cut as it may seem at first glance. Hugo (1983, 87) has argued that an important concept when considering the difference between permanent and circular migration is that of commitment. He argues that all migrants can be located along the continuum depicted in Figure 1 according to the mix of the degree of commitment that they have to their origin and that to which they feel toward the destination. To take an extreme example, an unskilled labourer circular migrant A moves from Indonesia to Malaysia with the intention of earning sufficient money to buy a small business in his home community. He leaves his whole family behind in Indonesia, he retains his Indonesian citizenship and his intention is that once he has reached his target earnings he will return to Indonesia and stay there. His commitment is almost totally to his Indonesian origin. On the other hand, B in the diagram is also Indonesian but she has obtained her high school and university education in medicine in Adelaide, Australia. During her study she has met a fellow doctor who she has married and had children with. Her parents have died so she only has distant relatives in Indonesia. She is an Australian citizen and sees her future and that of her family as being totally Australian. Her commitment to her Indonesian home which she left as a child is very limited.

These are cases near the extremes of migrants being almost totally committed to their origin or to their destination. However migrants can be located at any point along the continuum according to the relative mix of their commitments to the origin and their destination. Migrant C, for example, is an ethnic Chinese businessman who left Indonesia during the anti-Chinese riots of 1998 and took his family to Australia where he has set them up in Sydney. His children have gone to Australian schools and one has met and married an Australian partner. However he has retained his business interests in Jakarta and circulates regularly between Australia and Jakarta. He has developed business interests in Australia but still retains his Indonesian enterprise and his parents and siblings still live in Jakarta. His commitment is equally divided between origin and destination.

Nationalism assumes that immigrants forsake their heritage and origins and shift from X to Y quickly. In reality this is not common. Most movers retain a mix of commitment to origin while developing commitments to their destination. Indeed the concept of transnational families involves family members being physically distributed between origin and destination with a mix of commitments to the two. A key distinction between circular migrants and permanent migrants is that the former are located closer to X in Figure 1 while permanent migrants are closer to Y.

In most contexts it is possible to develop a number of indicators which could be used to measure the level of commitment to origin and destination for particular migrants. This could include, for example:

The location of family members – Leaving nuclear family members in the origin is a strong indication of maintaining a major commitment to the origin community while having extended family in the origin is also indicative of linkages, albeit less strong.

Maintaining full citizenship (or even joint citizenship) at the origin is a clear reflection of a strong commitment while temporary resident status at the destination is indicative of a weaker association than with the origin.

The location of property owned by the migrant is also reflective of their relative connections with origin and destination. This is especially the case for businesses, agricultural land and other fixed assets but house ownership is also of relevance.

The regularity and scale of remittances also is indicative of the strength of commitment to the origin community. Circular migrants tend to send more money home and more often since they usually are supporting the balance of their nuclear family that remains there.

The balance of locations of bank accounts and investments also is an indictor of the degree of commitment to origin and destination.

The ethnicity/ancestry of one’s partner can be another indicator of extent of commitment to the origin community. It is likely that where both partners come from the origin country that the family’s linkages home will be stronger than if one is a native of the destination.

Language can also be a relevant marker. The extent to which the origin language is spoken at home in day to day family communication can reflect the strength of identification with the origin. Similarly the ability of the immigrant with respect to speaking the destination country language can also be an indicator of the extent of commitment to origin and destination.

The extent of cultural maintenance can also be a gauge of the degree of commitment to the origin. This may be associated with active membership of migrant associations and organisations based in the destination country.

Voting rights and behaviour may also reflect the relative degree of commitment to origin and destination.

When taken alone and in isolation, each of these elements may be fallible as a direct indicator of the relative degrees of commitment to the origin and destination. If they are considered together they should give a clear indication of the relative strength of the two associations. The aggregate measure obtained can locate them along the continuum presented in Figure 1. Most first generation movers will not be at either of the extreme poles of total commitment to origin or destination but will have a mix of linkages with both. Circular migrants will be more to the left of the diagram and permanent migrants to the right. Seen in this way there are clear overlaps between circular and permanent migration.

The study of circular migration is hampered by a lack of data relating to its scale, composition and impact. Standard demographic measurement of migration stocks and flows predominantly captures movement on the far right of Figure 1. Accordingly the scale of non‑permanent movement is not appreciated and little evidence is available to policy makers to resolve policy dilemmas regarding it. Indeed as transnationalism has replaced permanent settlement as the dominant paradigm in international migration research (Glick-Schiller et al. 1992; Portes et al. 1999; Vertovec 2004) there is a growing disconnect between standard migration measurement and the actual nature of population mobility between countries. More than three decades ago Mitchell (1978: 6-7) pointed out, in relation to internal circular migration:

‘… the topic (circular migration) has in my opinion remained remarkably intractable to thorough-going analysis. Part of this analytical recalcitrance derives from the great difficulties in collecting suitable data to carry out adequate theoretical formulations’.

This judgement is equally applicable to the contemporary situation with respect to international circular migration.

CIRCULAR MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT: THE DEBATE

While circular migration has a long history it was the publication of the Global Commission on International Migration’s Report (GCIM 2005: 31) which has focused attention on its developmental significance:

‘The Commission concludes that the old paradigm of permanent migration settlement is progressively giving way to temporary and circular migration … The Commission underlines the need to grasp the developmental opportunities that this important shift in migration patterns provides for countries of origin’.

There have been arguments made that circular migration is better able to deliver development dividends and poverty reduction impacts of south-north migration for low income origin countries than can permanent relocation. This is predominantly because such migrants are more committed to their home community than their permanent counterparts because they usually leave their nuclear family at home and because they reside part of the time at the origin. Accordingly they are likely to remit a larger proportion of their income and are more likely to return to the home country and contribute to development.

Some countries in Asia have sought to encourage an upskilling of the temporary labour migrants leaving the country (e.g. Indonesia – Hugo 2008). The rationale here is that such workers will earn much more in destinations than their low skill counterparts and therefore are more able to remit larger sums back to their origins. In addition they are more likely to acquire training and experience at the destination which will enhance their skills than is the case with low skilled labour migrants. This logic however does have flaws:

High skill workers often remit smaller proportions of their income to origin communities partly because they tend to come from better off families (and communities) so that the level of need in the origin family will not be as great. Moreover these migrants are often able to bring their immediate families with them to the destination so that they are not as obliged to send back money to immediate family. As a result their level of commitment back to the home community may not be as great as it is for low skilled migrants.

Such migrant workers are more likely to come from cities and better off parts of origin countries (since they have higher levels of education and training) than low skill migrants who often come from poorer areas.

The loss of the human capital of some of these higher skilled temporary labour migrants may have negative effects in origin areas. In the Pacific for example it is apparent that the emigration of nurses and teachers to countries like Australia and New Zealand under temporary visas has had negative impacts on health and education systems in the Pacific (Voight-Graf 2008).

Since temporary skilled workers often are given access to applying for permanent residence and even citizenship at the destination they may not return to origin countries as much as low skilled migrants.

On the other hand there are aspects of higher skilled temporary labour migration which potentially could deliver development dividends at home.

As mentioned earlier, they earn more at the destination so that the amount they can potentially remit is greater.

They have the opportunity to enhance their skills and experience which can benefit the origin country when they return or while they are still away if they transmit new knowledge and ideas back to relevant groups in the home country.

Unlike low skill migrants they are more likely to maintain non-family network links with colleagues, professional organisations, etc. which can be the conduits through which new ideas and ways of doing things can be introduced to the home area.

They can enhance productive linkages for trade, investment, etc. between the origin and the destination.

There are few barriers to the international movement of highly skilled workers but it may be that it is the circular mobility of low skilled workers which can have the greatest impact in reducing poverty in origins.

The discussion on the preferability of circular migration to permanent settlement is usually cast in terms of the greater positive impact on origin communities. However, it is important that it be recognised that they also have some advantages from the perspective of receiving countries as well.

Firstly in terms of meeting receiving countries’ labour market shortages temporary migration permits greater labour market flexibility than permanent migration (Abella 2006). The particular labour demands that they meet may dry up. Singapore, for example, sees its low skilled migrant workforce in this way and at times of economic downturn the numbers of workers can be easily reduced. Similarly when demand for labour is seasonal, as in agriculture, temporary labour has some real advantages.

Secondly the influx of skilled workers on a temporary basis can allow a country to ‘buy time’ to train sufficient numbers of its native workers to do these jobs. The migrant workers can even play a significant role in providing that training formally or through ‘on the job’ training and skills transfer.

Thirdly from the perspective of ageing of destination country societies temporary migration may be advantageous. Migrants are always young and on their arrival in the country they have a ‘younging effect’ on the host population although this is very small given their small numbers in relation to the total population. However migrants age too. Hence if they remain in the country they will age with the host population and contribute to ageing. For example in Australia the long history of sustained postwar migration has meant that in 2006 the percentage of the overseas-born aged 65+ was higher for the overseas-born (19.0 percent) than the Australia-born (11.1 percent). Moreover the overseas-born population aged 65+ increased faster than their Australia-born counterparts over the 2001-06 period (3 percent per annum compared with 1 percent). Hence a ‘revolving door’ of migrant workers provides a constantly young workforce to the destination country without contributing to ageing of the workforce or population.

Fourthly, as Abella (2006, 2) points out, ‘compared to permanent immigration, liberalising temporary admissions is politically easier to sell to electorates that have come to feel threatened by more immigration’.

Fifthly, some countries have fears of social cohesion breaking down if immigrant communities settle permanently and there are difficulties of integration.

Hence if it can be established that circular labour migration can have beneficial effects for origin countries it can also often be a more acceptable migration option to destination communities as well.

These arguments have encouraged policy makers in high income nations and in multilateral agencies to recommend circular labour migration. For example, the European Commission (2007: 4) has examined:

‘… how circular migration can be fostered as a tool that can both help address labour needs in EU Member States and maximise the benefits of migration for countries of origin, including by fostering skills transfers and mitigating the risks of brain drain’.

Further, they have identified two main forms of circular migration which could be most relevant in the EU context:

Circular migration of third country nationals in the EU giving the opportunity for settlers in the EU to work in their home country while retaining their EU resident status.

Circular migration of persons living in a third country outside of the EU.

In New Zealand in 2007 the government announced a Recognised Seasonal Employer (RSE) Scheme which seeks to bring agricultural workers from Pacific countries for periods of up to 7 months to work on horticultural and viticultural holdings. As is pointed out by Ramasamy et al. (2008) while the scheme was designed to fill longstanding structural labour shortages it had an explicit objective of having positive developmental impacts in origin communities. In the first year over 5,000 workers were brought in mainly from the Pacific nations of Vanuatu, Tonga, Tuvalu, Kiribati and Samoa. The RSE program was developed cooperatively by the New Zealand Immigration, Labour and Development Assistance agencies in order to ensure that its developmental impact was maximised. The communities of origin are being studied longitudinally in order to assess the scale and nature of the developmental impact of the circular migration (McKenzie, Martinez and Winters 2008; Gibson, McKenzie and Rohorua 2008). In 2009 Australia introduced a similar pilot program.

Hence there has been a strong response to the GCIM’s (2005) plea to design circular migration programs which seek to have positive effects not only in filling labour shortages in the destination but also on development in origins and improving the lives of the migrant workers themselves. However there has been a strong critical voice which has argued that there is a significant body of evidence that circular migration programs can have negative effects in origin areas and on the migrant workers themselves. These have in particular drawn attention to the experience of the guestworker program of Europe in the 1950s and 1960s (Castles and Kosack 1973; Castles 2006a and b).

Vertovec (2006: 43) has summarised a number of concerns that need to be borne in mind in the rolling out of these new circular migration schemes. Prominent in these criticisms is that in practice such schemes lock migrants into dependent and exploitative relationships and offer little opportunity for upward mobility and training. Such programs often involve a loss of rights among the workers and they suffer lack of integration exposing them to exclusion. Others suggest that it encourages illegal ‘overstaying’ and creates substantial compliance problems for destination authorities.

In Asia and the Pacific the temporary labour migration of low skilled workers has been heavily criticised as being a ‘new form of indentured labour’. Some NGOs in the region even equate it with trafficking because of the exploitation of migrants that often characterises this movement. The undoubted excessive rent taking, social costs of long separation from families, lack of opportunities for social mobility and lack of opportunity to transfer to permanent residency are also criticised. It is also seen to be associated with undocumented migration. These criticisms all can be sustained by looking at particular migrants in particular flows of temporary low skilled labour migrants. However the question has to be asked as to whether the problems are intrinsic features of this type of migration or whether they are due to a failure to introduce fair and efficient governance of labour migration systems in the Asia-Pacific context. There is some evidence that it is the latter rather than the former.

In the region the potential for this type of migration to have a developmental impact is considerable not only because of their large numbers but also because most retain a strong commitment to their home communities where they leave their families. Accordingly they send back a higher proportion of their income in remittances than is the case for permanent settlers. Moreover they intend to return to their homelands and this is enforced by the migration regimes in destination countries. It has been shown (Hugo 2001) that in many countries (e.g. Indonesia) this type of migrant worker is drawn from some of the poorest areas of the country (e.g. parts of Java, East and West Nusatenggara). In such areas remittances are the only substantial inflow of potential investment money from the outside.

Given this substantial potential for international contract labour migration to deliver financial resources to the grass roots in some of the poorest areas in the region, what are the barriers which are dampening these impacts? One of the main issues here relates to transaction costs. For many contract workers the amounts that they have to pay to recruiters, to government officials, to travel providers, for documents, training, etc. are very high and well above what could be considered a reasonable charge for those services. There is too much unproductive rent taking in the burgeoning contract labour migration industry in the region and this is siphoning away money that migrants earn that otherwise would have gone toward development related activity in home areas. Often migrants have to work several months on arrival at the destination just to pay off the debts incurred by the migration process. If they are duped by recruiters so that the job they were promised is not available or if they cannot complete their contract for some reason they and their families have a substantial (and rapidly increasing) debt. Exploitation of migrant workers in the recruitment and preparation for travel processes, en route, at the destination and on their return home is rife. It should be noted that in some countries it is the documented migrants who have higher transaction costs than undocumented migrants. Indeed one of the reasons why migrants opt to take the undocumented route is to avoid the predations of gate keepers who extract money, both official and ‘unofficial’, at every stage of the migration process.

Migrant remittances are a key to labour migration having positive impacts on development and poverty reduction in origin areas. Yet these potential dividends can be reduced firstly by having to pay high rates to send the money home and by the lack of investment opportunities in the home area. It is apparent that despite a range of ingenious methods of sending money home, many systems overcharge migrants to remit money so that the proportion of earnings that eventually get back to the origin is smaller than it could be. In addition, Hugo (2004) found in Eastern Indonesia that the origin area of migrant workers to Malaysia had been so neglected by the central and provincial governments that it lacked the basic infrastructure which would be needed for the successful setting up of new enterprises by returned migrants. There were very few productive channels open to returnees to invest money in productive enterprises other than to purchase agricultural land or buy a passenger motor vehicle.

In short there is considerable evidence that in Asia and the Pacific that the potential for circular migration to deliver development dividends to origin areas is being compromised by the poor governance of these migration systems which prevails over much of the region. Examples of best practice in circular migration in the region exist but are few and far between. In particular the excessive costs of migration are diverting the earnings of the migrant workers which otherwise could have been directed to development related expenditure in the origin area. Moreover poor governance results in significant undocumented migration, lack of protection and exploitation of the migrant workers and destination communities developing anti-migrant attitudes and practices.

MISCONCEPTIONS OF CIRCULAR MIGRATION?

It was indicated earlier that the body of empirical knowledge of the scale, composition and effects of international circular migration in Asia is limited. In such a context it is easy for stereotyping and misrepresentation of circular migration and its effects to occur. In fact like other forms of migration its causes and consequences are complex. There is a tendency for some to label circular migration as bad because of the experience in Europe in the 1950s and 1960s and subsequently in parts of Asia. Equally, however, a blind insistence that its impacts are always beneficial is misguided. It is important, however, to seek to break down some of the stereotypes which have been assigned to circular migration. Field experience with such migrants over decades has convinced this researcher that circular migration is a more complex and nuanced process and one in which there can be beneficial outcomes for migrants although such outcomes are by no means assured. Some insights into the process can be gained from the considerable body of research relating to internal circular migration (Elkan 1967; Chapman 1979; Chapman and Prothero [eds.] 1985; Bedford 1973; Hugo 1978, 1982). This literature provides a number of insights into this form of movement which may have relevance for international migration. There are a number of ‘myths’ that have grown up around unskilled circular migration which some of the empirical evidence available suggests are at the very least contestable. These include the following:

‘There is nothing so permanent as a temporary migrant’. Certainly many temporary migrants see their move as a part of a longer term strategy to remain permanently at the destination. Yet for many others circular migration is a preferred strategy. Certainly there are sacrifices of separation from family but the idea of earning in a high income/cost context and spending in a low income/cost context is appealing as is the idea of remaining in their cultural hearth area. Circular migration can become a continuing and structural feature of families and economies and it doesn’t have to lead to permanent settlement. Moreover if there is a regime which facilitates migrant workers returning relatively frequently to their families as opposed to constraints which in fact make this so difficult that migrants opt for a permanent settlement strategy at the destination this will encourage circular migration. Where origin and destination are relatively close together, improved transportation makes regular home visiting increasingly feasible as is the case with internal circular labour migration (Hugo 1975, 1978). It must not be assumed that circular migration represents the initial stage of permanent settlement, especially if there is a migration regime which facilitates circular movement. Circular migration can be a sustainable continuing mobility strategy. Indeed there is evidence of the strategy being passed between generations.

‘Circular migrants lack agency’. Not all temporary labour migrants are victims of criminal syndicates, unscrupulous recruiters and grasping employers. Certainly there are many examples where exploitation is significant. Yet in fieldwork one is frequently impressed by the extent to which migrant workers are empowered and are highly skilled at using the existing circular migration regime to maximise the benefits for themselves and their families. Again, however, governance systems are of paramount significance. Migration is often selective of the most entrepreneurial and risk taking groups in a population. There is ample evidence that, given a fair system of governance, circular migrants are very capable of maximising the benefits they can derive from migration.

‘Circular migrants lack social mobility’. In many cases circular low skill labour migrants have considerably enhanced their position in the destination. For example, upward mobility and enhanced training is commonplace among East Nusatenggara migrants to East Malaysia (Hugo 2001).

The key point is that low skill circular labour migration can have positive outcomes for migrant workers and their origin communities. In fact it often does. However the regime for this type of movement in some Asia-Pacific countries is characterised by poor governance, corruption and lack of coherence so that these outcomes are compromised. The question becomes whether dealing with these issues effectively can enhance the positive effects in origin areas.

SOME LESSONS REGARDING CIRCULAR MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT[1]

With the increasing interest in circular migration by both migration and development agencies within government it is important that the institutions and programs that are put in place to facilitate this recognise that much of the experience of the past has resulted in less than optimal outcomes, especially for the migrants themselves. In the Asia-Pacific such programs have varied greatly in their quality and all too often corruption, exploitation and mistreatment of workers has resulted. Moreover the benefits delivered to origins have been diluted. It is important to learn from this experience not only so the new programs that are being rolled out are given the best possible chance to reduce poverty and facilitate development in origin areas but also for the much needed reform of many existing programs in the region. Can reform of the governance of temporary labour migration systems result in it becoming a significant contributor to development in origin countries? If so, what are the lessons of best practice in temporary labour migration systems in the region which would inform that reform? It is to these questions that we now turn.

Abella (2006: 53) has argued that while it is not possible to put forward best practices in circular migration that are applicable to all (or even most) countries and migration systems it is nevertheless possible to identify some of the elements which make for successful programs. In this section we will summarise some of these lessons. At the outset, however, we need to state that there is a fundamental need throughout the region to significantly improve governance of circular migration. While corruption, excessive rent taking, exploitation, denial of basic rights etc. are allowed to flourish, the developmental impact of circular migration will remain compromised. Hence what is required are over-arching sound governance systems which protect the interests of destination communities while also providing migrants with appropriate access to work, protecting their rights, making it possible for them to remit as much as possible of their earnings home and to return home in order to achieve win-win-win results.

We will briefly consider here some of the lessons of best practice in circular migration programs in the Asia-Pacific region. However, a couple of initial comments are required. Firstly, we need to reiterate that there is no single recipe or blueprint that is applicable in all situations. Circular migration structures, institutions and programs should be a judicious mix of best practice lessons and considerations to the specific context. Our focus here is predominantly on low skilled migration since for the most part skilled workers are in demand and have more bargaining power than their low skilled counterparts (Ruhs and Martin 2008). The lessons of best practice need to be applied in both origins and destinations.

One of the necessary elements of best practice identified by Abella (2006: 53) relates to the proper management of labour demand in destination. Circular migration must be responding to real labour shortages and not used by employers to drive down the conditions of local workers. This is not an easy task but Abella (2006) argues that there needs to be robust forecasts of long term labour supply deficits in specific areas. These need to be combined with practical methods of including circular migration as one of the elements to respond to the current needs of industry.

Selection of workers so that they have not only the specific skills and training required of the work but also the personal attributes to be able to adjust to life at the destination is important. There must be total transparency in the selection criteria, process and costs. It is at the initial recruitment and selection stages in Asia and the Pacific that many of the problems of excessive transaction costs are incurred. Too often migrant workers and their families go into debt to meet the costs which are imposed and this is a major barrier to the earnings of migration being invested in development related or poverty reduction activity. This is complicated by the fact that in several countries there are a plethora of agents, subagents, middlemen, travel providers and officials that are involved in the recruitment and preparation process and imposing charges – some legitimate, others not. An obvious goal is to reduce these transaction costs to a level commensurate with the services provided and there are a number of practices which can help achieve this – providing accurate and comprehensive pre-departure information and training, keeping processing efficient, effective management and regulation of agents, providing low cost loans to fund travel and involvement of employers in the selection process.

The success of temporary labour migration, while it can be strongly shaped by the recruitment and predeparture experience, hinges mostly on their experience in the workplace and society more generally at the destination. While the country of origin can influence this through developing MOUs (Memoranda of Understanding) on conditions of workers, setting up mechanisms like labour attaches and branches of national banks in destination countries, their power and influence is strictly limited by diplomatic practice and protocol. The employers and governments at destinations have a high level of influence in shaping the experience of migrant workers and there is a need for a conceptual leap among policy makers in most destinations to begin to factor in to their deliberations the possible effects of their policies and programs not only for their own communities, employers and countries but also those for the immigrant workers themselves and development impacts in origin communities. While governments lack jurisdiction in destination countries, NGOs (Non-Government Organisations) can often effectively bridge origin and destination countries by working closely with different, but related, NGOs established in the destination.

In considering best practice in relation to labour migrants’ experience in destination countries we will examine the roles of sending and receiving countries separately. However it is important to underline that best practice would involve a high level of cooperation between the governments of sending and receiving countries on these issues involving:

An MOU which specifies the conditions under which labour migrants are accepted into a country, their minimum conditions, rights and obligations (and those of their employer) etc.

A mechanism to allow regular discussions between the countries on migrant issues.

A mechanism through which there can be timely and effective action decided upon to deal with pressing specific issues relating to migrant workers.

An open channel of communication between governments in which there can be frank regular interchange and discussion of migrant worker issues.

Most fundamental to best practice in circular migration systems is full protection of migrant workers, basic rights and safety in origin, en route and destination countries. This involves all stakeholders involved in the process. Abella (2006) also identifies some other elements in the conditions of employment:

Flexibility in determining periods of stay to allow for differences in the type of work to be performed and conditions in the labour market.

Allowing for change of employers within certain limits.

Avoiding creating conditions (i.e. imposing forced savings schemes, employment of cheap labour though trainee schemes) which will motivate migrants to opt for irregular status.

Remittances are the raison d’etre of most circular migration. Best practice in both origin and destination countries involves educating migrant workers and potential migrant workers about all of the alternatives for sending money home and above all the making available of lower cost and more secure options. The sending country can support this by encouraging national and other banks from the home country establishing low cost channels for remittances and setting up establishments in the major destinations to facilitate sending money back. Particular notice should be taken of new low cost alternatives including cell-telephone based remittances (World Bank 2006, 150). Familiarising migrant workers with remittance systems and involving them in them can be their first step toward ‘financial literacy’ and involvement in the formal financial system which can be of help to them in the future (Terry and Wilson 2005).

One dimension of international temporary labour migration which is often overlooked is the social costs which are endured by the migrant and their family by extended separation (Hugo 2004). There may be a role for sending governments in ameliorating the social costs on the family that remain behind. At present it is the extended family, community solidarity and NGOs that provide support, however governments may also be able to play a role. Although sending governments can play a role in the protection and support of circular migrants in other countries, the migrant experience in destinations is influenced more by employers, governments and society in those destinations. Governments play a central role because they set the conditions under which migrant workers can enter their country and the rights, access to services and obligations which they have while in the country.

An important element in best practice of destination countries involves the setting up and administration of regulation of employers of circular migrants. Best practice here seems to involve granting special status to employers who have a good reputable history of abiding by regulations and fairness in dealing with migrants. This status involves less complex application for workers and reporting. However for other employers, inspection and full compliance with regulations is necessary. Moreover employers that repeatedly fail to meet the requirements of regulations should be banned from employing circular migrants. Best practice involves adopting a system of labour inspections to meet the specific problems of migrant workers.

Return to the home country is a fundamental characteristic of circular migration and can be crucial in determining the extent of the developmental impact of that migration. The destination country is involved to the extent that it can facilitate the termination of work and travel to the homeland to be as secure and inexpensive as possible. In some contexts of Indonesians in Malaysia employers refuse to pay the full wages (some of which are often retained by the employer) or to return their passport without payment. The imposition of unauthorised charges on accommodation, transport etc. is also common at this stage. In cases where the migrant workers have been contributing to compulsory (or voluntary) pension schemes full portability is best practice. It has been known that criminals cluster in transport points and border crossing areas to prey on returning migrant workers so it is imperative to provide secure passage in such situations.

Nevertheless, it is predominantly the responsibility of the origin country and the community to provide the context in which the returning migrant worker can have maximum impact on local, regional and national development. As is the case with destination countries facilitating the safe and free return to the home community is an important part of best practice. However this is not always the case. In Indonesia, for example, legal labour migrants are compelled to return through infamous Terminal 3 at the Jakarta airport. Here they are subject to a number of imposts, official and unofficial (Silvey 2004). They are compelled to return to their home area using a sanctioned carrier at an inflated price. Such practices are to be deplored and best practice would instead facilitate a speedy and safe return to the home area.

Another element relates to the interpretation of the ‘temporariness’ of circular migration. Most programs have a maximum time that a worker can work at the destination under a contract before returning home. Some allow one renewal of a contract without returning but most insist on return after the initial contract time expires. Thus regulations can have the effect of migrant workers ‘running away’ from their employer and becoming undocumented because they fear that they will not have access to jobs in the destination in the future. It would seem to be best practice to facilitate return or repeat labour migrations. In the case of the New Zealand RSE Scheme it seems that the majority of the initial group of seasonal migrant workers will be, or have been, offered second year contracts. Clearly in that case many employers see the continuity as beneficial because the workers have acquired the appropriate skills, attitudes to work, local knowledge etc. The idea of temporary labour being a more or less permanent strategy (at least for the key younger working ages) for many low skilled Asia-Pacific migrants needs to be investigated. Potentially, at least, it would seem to have advantages for:

The migrant in that they have an assured source of income for longer than a couple of years. It also provides a greater opportunity for training than would be the case in a one-off labour migration.

The employer gains continuity and a greater degree of experience and skill which provides productivity dividends.

The origin in that there is a greater flow of remittances and potentially a chance to improve the stock of human resources skills through extra training of migrants.

In addition it may have compliance implications because it reduces the number of runaways because the migrant worker can be assured of access to work in the destination over an extended period while remaining within the legal system.

Ruhs (2006, 30) has pointed out a temporary labour migrant program can never give an upfront guarantee or even raise the expectation that a worker admitted under the program will eventually and inevitably acquire the right to permanent residence in the destination. However this does not

‘preclude the possibility that the host country might facilitate a strictly limited and regulated transfer of migrants employed as TMPs into permanent residence based on a set of clear rules and criteria’.

Clearly a sound migration policy should comprise a judicious mix of both permanent and temporary migration possibilities.

CONCLUSION

Circular migration is increasingly being seen by sending countries, receiving countries and multilateral migration and development agencies as a desirable mobility strategy. However policy development in this area is being carried out with little assistance from evidence of the nature, significance and effects of the phenomenon. Accordingly, Vertovec (2006: 44) rightly concludes his careful analysis of circular migration on a strong role of caution:

‘For sending countries, receiving countries and migrants themselves, mutual gains may indeed be had if circular migration policies become manifest. Moreover, as recent policy documents suggest, circular migration policies might positively contribute to tackling challenges around economic development, labour shortages, public opinion, and illegal migration. Yet when considering anything – particularly an approach to global policy – that portends to be a kind of magic bullet, caution should certainly be taken. The “wins” of the win-win-win scenario may not be as mutual as imagined’.

Yet this caution must be equally exercised by the opponents of circular migration as it should by the proponents. There is strong evidence that circular migration can have positive effects on development in the origin. However the fact is that these impacts do not occur as a matter of course. Indeed in many contexts they are not felt, or hardly at all. For development dividends and poverty reduction effects to be achieved and maximised in Asia and the Pacific will require a major improvement in the governance of circular migration systems. There is an urgent need for the reform of these systems and to achieve this will not be easy.

More or less effective circular migration systems exist in most OECD countries but they apply largely to highly skilled workers. One of the features of their immigration systems over recent years has been the introduction of ‘skill friendly’ visa and immigration regimes which facilitate the coming and going of skilled workers. However, few countries extend this to lower skilled workers. Yet the reality of emerging labour demands in ageing OECD workforces is for a mix of higher and lower skilled workers. The extent of such demands needs to be definitively established and migration regimes put in place which match those needs. Most contemporary high income societies with low fertility and ageing populations are likely to need immigration policies which enhance both permanent and temporary movement of both skilled and unskilled workers.

Circular migration is certainly not a development ‘silver bullet’. It is no substitute for sound economic policy, good governance and progressive human resource policies in origin countries. However it can be a positive contribution to improving the lives of people in low income nations and gaining a more nuanced and deeper understanding of how this occurs in an important research priority.

The article was originally published in the book Boundaries in Motion.

REFERENCES

Abella, M., 2006. Policies and Best Practices for Management of Temporary Migration. International Symposium on International Migration and Development, UN Population Division, Turin, Italy, 28-30 June.

Bedford, R.D., 1973. New Hebridean Mobility: A Study of Circular Migration, Department of Human Geography, Australian National University, Canberra, Publication H9/9.

Castles, S., 2006a. Back to the Future? Can Europe Meet Its Labour Needs Through Temporary Migration? International Migration Institute Working Paper No. 1, Oxford.

Castles, S., 2006b. Guestworkers in Europe: A Resurrection?, International Migration Review, 40, 4: 741-766.

Castles, S. and Kosack, G., 1973. Immigrant Workers and Class Structures in Western Europe. London: Oxford University Press.

Chapman, M., 1979. The Cross-Cultural Study of Circulation, Current Anthropology, 20, 11: 111-114.

Chapman, M. and Prothero, R.M. (eds.), 1985. Circulation in Third World Countries. London, Boston, Melbourne and Henley: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 473 pp.

Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC), 2008. Immigration Update 2007-2008, AGPS, Canberra.

Elkan, W., 1967. Circular Migration and the Growth of Towns in East Africa, International Labour Review, 96, 6: 581-589.

European Commission, 2007. Circular Migration and Mobility Partnerships Between European Union and Third Countries. Memorandum 07/197, 16 May 2007.

Gibson, J., McKenzie, D. and Rohorua, H., 2008. How Pro-Poor is the Selection of Seasonal Migrant Workers from Tonga Under New Zealand’s Recognised Seasonal Employer Program, Pacific Economic Bulletin, 23, 3: 187-204.

Glick-Schiller, N., Basch, L. and Szanton Blanc, C., 1992. Transnationalism: A New Analytic Framework for Understanding Migration, pp. 1-24 in N. Click Schiller, L. Basch and C. Szanton Blanc (eds.), Toward a Transnational Perspective on Migration, New York Academy of Sciences, New York.

Global Commission on International Migration (GCIM), 2005. Migration in an Interconnected World: New Directions for Action, Report of the Global Commission on International Migration, Switzerland.

Global Commission on International Migration (GCIM), 2007. Circular Migration and Mobility Partnerships Between the European Union and Third Countries, http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=Memo/07/197.

Hugo, G.J., 1978. Population Mobility in West Java. Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University Press.

Hugo, G.J., 1982. Circular Migration in Indonesia, Population and Development Review, 8, 1: 59-84.

Hugo, G.J., 1983. New Conceptual Approaches to Migration in the Context of Urbanization: A Discussion Based on Indonesian Experience, pp. 69-114 in P.A. Morrison (ed.), Population Movements: Their Forms and Functions in Urbanization and Development, Ordina Editions for the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population, Liege.

Hugo, G.J., 1994. The Economic Implications of Emigration from Australia. Canberra: AGPS.

Hugo, G.J., 2001. Labour Circulation and Socio-Economic Transformation: The Case of East Java, Indonesia, by E. Spaan, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 37, 1, April.

Hugo, G.J., 2004. International Labour Migration and Village Dynamics: A Study of Flores, East Nusa Tenggara, pp. 103-133 in T.R. Leinbach (ed.), The Indonesian Rural Economy: Mobility, Work and Enterprise, Institute of South East Asian Studies, Singapore.

Hugo, G.J., 2008. Migration Management: Policy Options and Impacts on Development: An Indonesian Case Study. First draft of a paper for the OECD Development Centre, September.

Hugo, G.J., forthcoming. Best Practice in Temporary Labour Migration for Development: A Perspective from Asia and the Pacific, International Migration, accepted for publication on 9 March 2009.

Hugo, G.J., Rudd, D. and Harris, K., 2001. Emigration from Australia: Economic Implications, Second Report on an ARC SPIRT Grant, CEDA Information Paper No. 77.

King, R., 2002. Towards a New Map of European Migration, International Journal of Population Geography, 8, 2: 89-106.

Klanarong, N., 2003. Female International Labour Migration from Southern Thailand. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Population and Human Resources, Department of Geographical and Environmental Studies, University of Adelaide, March.

McKenzie, D., Martinez, P.G. and Winters, L.A., 2008. Who is Coming from Vanuatu to New Zealand Under the New Recognised Seasonal Employer Program?, Pacific Economic Bulletin, 23, 3: 205-228.

Mitchell, J.C., 1978. Wage Labour Mobility as Circulation: A Sociological Perspective. Paper presented to the International Seminar on the Cross Cultural Study of Circulation, East-West Centre, Honolulu, April.

Newland, K., Agunias, D.R. and Terrazor, A., 2008. Learning by Doing: Experiences of Circular Migration, Insight, September.

Portes, A., Guarnizo, L.E. and Landolt, P., 1999. The Study of Transnationalism: Pitfalls and Promises of an Emergent Research Field, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 22, 2: 217-237.

Ramasamy, S., Krishnan, V., Bedford, R. and Bedford, C., 2008. The Recognised Seasonal Employer Policy: Seeking the Elusive Triple Wins for Development Through International Migration, Pacific Economic Bulletin, 23, 3: 171-186.

Ruhs, M. and Martin, P., 2008. Numbers vs Rights: Trade-Offs and Guest Worker Programs, International Migration Review, 42, 1: 249-265.

Terry, D.F. and Wilson, S.R., (eds.), 2005. Beyond Small Change: Making Migrant Remittances Count. Washington: Inter-American Development Bank.

Vertovec, S., 2004. Migrant Transnationalism and Modes of Transformation, International Migration Review, 38, 3: 970-1001.

Voigt-Graf, C., 2008. Migration, Labour Markets and Development in PICs. Presentation to Conference on Pathways, Circuits and Crossroads: New Research on Population, Migration and Community Dynamics, Wellington, 9-11 June.

World Bank, 2006. Global Economic Prospects 2006: Economic Implications of Remittances and Migration. Washington DC: World Bank.

Zelinsky, W., 1971. The Hypothesis of the Mobility Transition, The Geographical Review, LXI, 2: 219-249.

[1] For a more comprehensive treatment of lessons of best practice from Asian labour migration, see Hugo (forthcoming).

Graeme Hugo is the University Professorial Research Fellow Professor of Geography and Director of the National Centre for Social Applications of GIS The University of Adelaide.